Greek Paradise, Lost

Travel Stories: In the Aegean isles, Dan Saltzstein went in search of a mysterious cave. He found it -- and a dose of danger.

09.21.11 | 11:56 AM ET

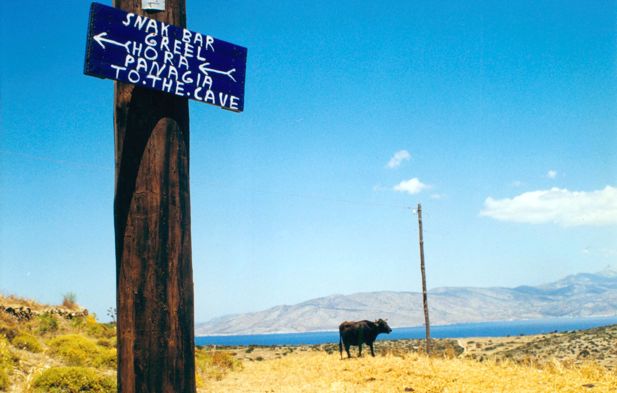

Irakleia, Greece (Photo by Dan Saltzstein)

Irakleia, Greece (Photo by Dan Saltzstein)Pulling into Aghios Giorgios, the main port on Irakleia, a tiny island in the Aegean Sea, I was, to my surprise, not seasick. This was a change from previous ferry trips I had made in the Cyclades, the sprawling group of Greek islands south of Athens. In the open waters between, say, Syros and Sifnos, a combination of big, choppy waves and ferries not much bigger than my Prius often resulted in me stumbling onto piers looking about as blue-green as the Aegean waters.

But Irakleia, nine square miles of rocky terrain with a permanent population of about 130, is sheltered from northerly winds by the significant bulk of Naxos, to the north. Naxos is a major tourist destination, but also the setting for some real-deal mythology. It’s where Theseus abandoned Ariadne, and where she ultimately got down with the god Dionysus. Irakleia, on the other hand, isn’t mentioned in mythology, and isn’t much on tourists’ radar either.

There’s a great line from a Don DeLillo book: “We’re all drawn to the idea of remoteness. A hard-to-reach place is necessarily beautiful, I think. Beautiful and a little sacred maybe.”

This, I suppose, is what I hoped to find on Irakleia.

It was 1998. I was about two-thirds of the way into a six-month trip through North Africa and Europe. Circling the Mediterranean, I landed in Athens and island-hopped my way down to Naxos. Soon, all the islands began to blend together, with their uniformly lovely beaches, white-washed villages, ancient ruins and unadorned grilled fish. All good things but, it seemed to me, interchangeable. So I took the thrice-weekly ferry from Naxos to Irakleia, which my guidebook described as “the least spoilt of the Cyclades.”

On top of those 130 or so residents, there were exactly six tourists: myself; Shane, a pleasantly bitter Irishman who left mysteriously after a few days without saying goodbye; Marianne, a lovely Dutch woman; her bushy-haired and bearded husband, whose name I never got, since, on my first night there, after downing his umteenth Amstel, he fell off his stool at the town’s one taverna and was bedridden the rest of the week; and a warm Belgian couple, neither of whom were actually Belgian. Steve, the tall, strapping husband, was London-born but now a mail-carrier in Antwerp; his strikingly lovely wife, Anushka, was Hungarian.

I found a beachside cabana—right next to one occupied by Steve and Anushka—run by a diminutive woman probably in her 60s, who reminded me, to an uncanny degree, of my Hungarian grandmother.

My first night on the island began with a World Cup match at the island’s taverna, Maistrali. This was the year that France not only hosted the tournament, but trounced powerhouse Brazil in the finals to win its first-ever Cup. During my trip, when I often felt disconnected from my surroundings, the Cup was always available as a comfort and ice-breaker with locals or European travelers I met along the way. (As a soccer—sorry, football—novice, it was also a terrific introduction to the sport.)

That night, Germany beat the then-fledgling U.S. team 2-0. The evening ended at the taverna with circle dancing, lots of retsina, ouzo and, for me, a probably ill-advised but uneventful night swim.

A couple of days later, Steve and Anushka invited me on a hike across Mount Papas, at the island’s far, eastern end, and to the Caves of Aghios Ioannis, about which we knew little. It wasn’t mentioned in my guidebook.

In the ridiculously exhaustive, 20-volume McGilchrist’s Greek Islands, Irakleia merits just five pages. “The walk to the cave,” writes Nigel McGilchrist—in italics, I might add—“is tough and there are no springs. Allow an hour and a half each way, and bring a powerful torch for the cave interior.” I believe I was wearing Teva sandals that day, brought no water, and the only source of illumination I had was one of those five-inch flashlights, which are fine, assuming you only need to see a foot in front of you.

And yet, we were soon hauling ourselves up bare, dry hills, passing the occasional cow or goat. We found a sign that read—in English, for some reason—“Snak bar,” “Greel,” and “to the cave,” with an arrow pointing vaguely in the direction we were heading. (We never found the snack bar or grill.)

The fact that Mount Papas is only about 1,400 feet high was cold comfort to my Teva-clad feet. We scrambled up one chalky rock incline after another. The views were spectacular—we could see Naxos from here, as well as the Lesser Cyclades that surrounded it, huddled close amid a deep, sparkling blue.

After a while, we came to the eastern end of the island. A sheer cliff dropped away beneath us, water crashing against its base. To our left were the entrances to the Caves of Aghios Ioannis, set back in a hillside cleft. The cave to the left had a reasonably sized entrance, which—for reasons lost to me now—didn’t interest us. The entrance to the cave to the right was barely bigger than the size of a human torso. A small bell hung above it.

“Beautiful and a little sacred,” DeLillo wrote. The mysterious cave held the promise of both.

Anushka, who had told me earlier that she had mild claustrophobia, had no intention of entering. Steve, who stood about 6’2” and probably had 80 pounds on me, was game. He wriggled through the entrance on hands and knees and I followed.

The cave, of course, was almost entirely pitch-black. I had my tiny flashlight—that, and the minimal light from the entrance, revealed a table stocked with matches and candles. But, for some reason, those three-inch-tall birthday-cake-sized candles. A few Greek Orthodox icons conveyed that this was some sort of Christian-era religious sanctuary, but there was no other information provided. Steve lit one of the tiny candles, which looked ridiculous in his big, meaty English hand. I pointed my flashlight into the cave, but its illumination faded quickly.

I could see the outlines and shadows of stalactites and stalagmites, and that the ground was slippery with dripping limestone. But I had no sense of how big the cave was, or where to head. Steve and I sort of shrugged at each other and went forward—him with his birthday candle, me with my tiny flashlight. We stepped slowly and precisely, with no sense of what was five feet in front of us.

Steve went first, with me pointing the flashlight at his shuffling feet. We were silent, tense with anxiety over the unknown terrain. After about 20 feet, we hit an incline and Steve scrambled up it. This was the moment I would later regret. “That seems like a bad idea.” I thought it, but I didn’t say it.

He took one additional step and suddenly, he was gone. All I saw was the tiny flame of his birthday candle drop and disappear. He had fallen off whatever precipice he was on, and I had no idea how long the drop was.

I was frozen with fear. Had I just witnessed the death of a guy I had just met a few days before? What would I tell his wife, waiting outside, ignorant of our circumstance?

And then, a soft voice: “Dan? I think I’m hurt.” He wasn’t dead. And I could tell by the sound of his voice that he hadn’t fallen a long distance. Yet he was out of sight and the last thing I planned to do was follow him up the slippery incline.

“Steve!” I yelled. “Are you OK?”

“I’m hurt,” he yelled back. “My leg’s hurt.”

Oh god, I thought. He broke his leg. We were probably 90 minutes from town, across rocky terrain, and the sun was going to start to set in an hour or so. I began to reel.

After a pause: “I think I’m OK.” I heard him scramble to his feet. I don’t know if I trust my ability to gauge distance by sound, but if I had to guess, I’d say he was 20 feet away. He clammered up the other side of the incline. Slowly, very slowly, we walked to the entrance and wriggled out.

The next few minutes, frankly, are hazy. I went into some sort of crazed survival mode, based, I should add, on zero actual training. I was the one, let’s remember, wearing Tevas.

Steve sat with this leg extended, poking at it to assess damage. I remember becoming convinced that I needed to make him a handmade splint. This was pre-“Survivor” or “Survivorman” or whatever; I don’t know where I would have gotten that idea, but I was thoroughly convinced. I found a gnarled—but very much alive—little tree and began to try to detach a branch. I pulled it back and forth, but it was not coming off. I was feeling progressively more desperate.

I looked down the cliff ahead of us. There was no place for a helicopter to land. And a helicopter from where? Naxos? Could we lower him down on to a boat—probably a 100 foot drop? And after sundown?

I couldn’t carry him back. No way. He was too heavy and the terrain was rocky and splintered.

At this point, I went into a panic blackout. Somehow, Anushka and Steve calmed me down and he started to flex his leg. “Maybe I can walk on this,” he said. “I can walk on this.” Pause. “Let’s just try to walk back.”

Steve or Anushka weren’t freaking out, I was. I finally gave up on my splint project and sat down to rest.

“It’s OK,” Anushka said calmly. “We’ll make it back.”

“Look, Dan,” said Steve, standing up and taking a few steps, with just a slight hobble and a wince as he did. “I can walk on this.”

Even in the moment, I realized how pathetic this all was.

I don’t remember much about that walk back. I was in a constant state of low-level panic, scared that at any point I might trip or fall. And then what? An image flashed in my head, of Anushka carrying Steve in one arm and me in the other, like some sort of female, Hungarian Paul Bunyan. I carefully placed one foot in front of the other, all the while keeping an eye on Steve’s progress, which was slow but uneventful.

Just as dusk began to descend, we arrived back at the village. Our fellow tourists were at the taverna. Italy beat Cameroon. I self-medicated with ouzo and stumbled the 10-minute walk to the cabana. Steve was resting and already talking about where he might get his hands on some pain killers. Not on Irakleia, I was sure.

The next day I left for Santorini.

A few weeks later, I was on to Belgium. I took a long trip on a suburban rail line outside of Antwerp, to Steve and Anushka’s warm, narrow house. We had drinks in their backyard and I slept in his step-daughter’s room. She was with her mother in London.

Steve was on disability; I learned that it was his back, not his leg, that was the problem. He could walk, but his normally impressive gait was stilted. Apparently, there was a substantial disability check involved. I asked if that was typically Belgian. “It would have been the same in England,” he said.

A week or so after I left Antwerp, I arrived in Paris, the day after France won the World Cup.

In the end, all was well. Steve would slowly recover, as would my nerves. But I had discovered—albeit glancingly—the other side of the off-the-grid coin. Paradise, it turns out, can be dangerous. Sort of.![]()