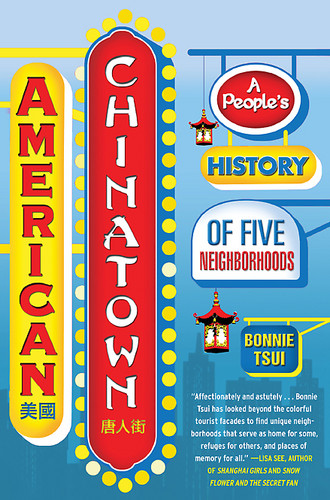

Interview with Bonnie Tsui: ‘American Chinatown’

Travel Interviews: Jenna Schnuer talks to the author of a new book about American Chinatowns and why "broken Chinese is the mark of being Chinese American"

10.07.09 | 10:07 AM ET

Photo by Matthew Elliott

Photo by Matthew ElliottThere has always been a Chinatown in Bonnie Tsui’s life. Though she was raised on New York’s Long Island, Tsui writes in her book, American Chinatown: A People’s History of Five Neighborhoods, that it was Manhattan’s Chinatown where her family went “to be Chinese.”

After moving to San Francisco in 2003, Tsui realized that, though the neighborhood’s name was the same, the Chinatown of her new home city had little to do with the one she had left behind. And, with that, she decided it was time to find out what makes a Chinatown.

For “American Chinatown” Tsui explored the people, history and culture of Chinatown neighborhoods in five U.S. cities—San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles, Honolulu and Las Vegas. I asked her about it via email.

World Hum: Since visits to Chinatown have always been part of your life, what was it like to look at the neighborhoods in a new way? Did you enjoy it?

Bonnie Tsui: Absolutely. It was a lot of fun to turn a reportorial eye to a place and a people who don’t usually get much in-depth investigation. People were very surprised that I was interested in their stories, and little by little, they really opened up. Many had never thought about their Chinatown experiences in any serious way, and I think they felt liberated by the chance to remove themselves a bit from the day-to-day, and talk about how they feel about their lives there.

In the book you make it clear that there are big differences in the personalities of different Chinatown neighborhoods around the U.S. Did that surprise you? What differences stood out for you?

I knew that there had to be differences in personality; what they were exactly I didn’t know until I started exploring the neighborhoods more thoroughly. For me, the founding stories—the backstory behind each place—were the most fascinating: how each community came to be what it is today, and how those currents still influence the neighborhood.

I was amazed to find that L.A.’s Chinatown, for example, had been formed so directly with influence from Hollywood. For instance, one incarnation of Chinatown had film sets lifted from The Good Earth, built by engineers and construction guys from the Paramount lot. And the ideas put forth by those movies influenced how the Chinese Americans in the neighborhood were perceived by the larger society around them.

Beyond the five you write about, where are some of the most surprising Chinatown neighborhoods in America? Any you haven’t visited yet that are high on your must-get-there list?

Some of the most surprising Chinatowns are the frontier communities of the railroad era that are no longer populated but have great historic value: Locke, Weaverville, Riverside, Woolen Mills in San Jose. There were also a number of underground Chinatowns in the West, with elaborate passageways and tunnels to hide the Chinese from hostile outsiders. Oklahoma City’s underground Chinatown was discovered during a 1969 excavation to build a convention center.

I’d love to poke around some of these sites, but they certainly have a different feeling than a vibrant living community, which is what I find the most interesting.

Who are some of the most unforgettable people you met while reporting the book?

I loved talking to the kids the most—they were so honest and straight-up with their commentary on living in Chinatown. Some of the most compelling moments in the book come with teenagers: one boy told me that his parents always talk to him in Chinese even though he talks back to them in English—he says that “broken English is a mark of a new immigrant, but broken Chinese is the mark of being Chinese American.” That characterization was really poignant for me—that it should be less a mark of shame than a signifier of a reality and an identity that isn’t really being understood by the older generations.

One girl, Rosa, showed me the tiny single-room occupancy apartment that she lived in as a kid growing up in San Francisco’s Chinatown; this was an 8-foot-by-10-foot room she shared with her parents and sister. Appallingly cramped conditions, but this is the reality for many residents of Chinatown.

What do you think is the future of Chinatown neighborhoods in America? Continued growth? New ones popping up?

I think the future of Chinatown relies, as it always has, on a continuing influx of working-class Chinese immigrants with little education and little English; they come here to seek a better life, and the freedom to work and have children who will have better opportunities than they did. They also come to reunite with family members already here, a phenomenon that sociologists call chain migration. All of these factors have been feeding American Chinatowns ever since their inception; all of these things keep Chinatown vibrant and thriving with people who seek out the neighborhood to fulfill their needs.

Things are certainly changing in China, with the rise of a middle class that never existed before; people have better opportunities there than they ever did, and many have no need to come to the U.S., and certainly not through Chinatowns if they already speak English and have jobs elsewhere. But there are still vast swaths of rural poor in China, and as long as the filial network continues to bring in immigrants through Chinatown, the neighborhoods will go on, growing and changing as the population streams do.![]()