Interview With Greg Mortenson: One Traveler Changing Lives

Travel Interviews: David Frey asks the bestselling author about the "Three Cups of Tea" approach to travel and life

06.04.10 | 10:46 AM ET

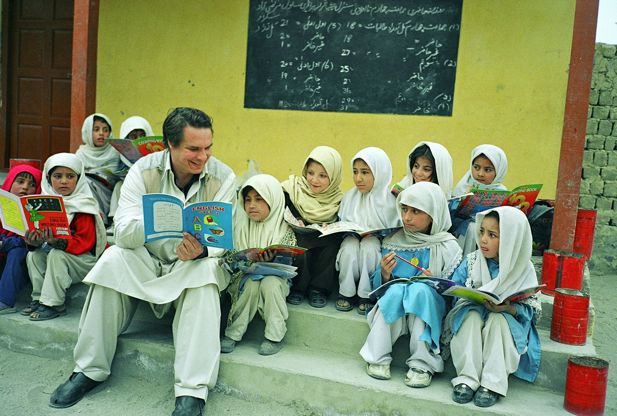

Greg Mortenson in Pakistan

Greg Mortenson in PakistanSince surviving a failed climb on Pakistan’s K2 in 1993, Greg Mortenson has dedicated himself to educating children—especially girls—in remote regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan. His books, Three Cups of Tea and Stones into Schools, have become bestsellers, and his organizations, the Central Asia Institute and Pennies for Peace, have helped educate some 60,000 children.

I caught up with Mortenson at the Telluride MountainFilm festival, where a stage version of “Three Cups of Tea” was debuting.

World Hum: Through the schools you’ve helped build in Afghanistan and Pakistan, you’ve made a powerful connection with people who a lot of Americans feel are their enemies. What have you seen in these people that so many others haven’t?

Greg Mortenson: I’ve worked in rural Afghanistan and Pakistan for 17 years now. I’ve traveled a lot. I grew up in Tanzania for 15 years. So I’ve spent a lot of time overseas. I find that people, we’re about 95 percent the same. We tend to judge people by the differences, which I say are about 5 or 10 percent. Maybe that’s a different way I look at people.

Does travel necessarily open minds to other cultures or do we end up bringing our own perceptions with us?

I think travel is good in any capacity. I do hope that people who travel to other countries spend at least a little bit of time not traveling in an isolated, encapsulated kind of way. Over the last two or three decades, travel, whether in wilderness or urban travel, has become much more insular. We have the Internet. We have GORE-TEX. We have vaccines. We can go anywhere as if we live in a capsule.

When I travel, I tend to not bring very much baggage with me, maybe just a carry-on. I also know that where I’m going, millions of people have lived for thousands of years. I know that I can survive there if they can survive.

I deal with people who, when they travel, have hundreds of lists and check-off items. I tell them, “Ninety-five percent of the things on your list you could probably get overseas in some form or another.” It’s not the end of the world if you don’t have your hand-held crank tool that you might think you need overseas. But that does take some perceived risk, or maybe letting go a little bit. Or maybe having some humility and appreciating other peoples’ perspectives and how they do something.

With all the traveling you do, is it still a pleasure for you?

I love to travel overseas. In the U.S., we’re so genericized with everything, so familiarity does kind of breed confidence. When somebody from the U.S. is used to traveling and having the Internet in the hotel room or a gym or a turkey sandwich for dinner, it’s a little bit of a leap when they go overseas.

I think it’s important when you travel that you get unplugged a little bit. I think we try now, with cell phones and the Internet, to stay connected all the time. I think some sort of disconnect from that, for just a few days or a week, can really enhance travel. You don’t have to be connected every day. I also find when I’m overseas for several weeks or months, I’m not in touch with the news. I don’t see it or hear about it. I find when I come back to the States, nothing has changed very much. The reality is, the news that we want to know every day maybe doesn’t really matter after a few weeks or months. Life goes on.

Any favorite places that you’ve visited?

I love my home in Montana. My ancestors were homesteaders in Montana, and I have lived in Bozeman since 1995.

I love the Karakoram mountains in northern Pakistan. I also love the Pamir mountains in the Hindu Kush range. Most of what I like are mountains. I do like a few beaches, but mostly I’m a mountain person. The Karakoram is the greatest consolidation of high peaks in the world. Within a 100-mile area, there are 65 peaks above 24,000 feet.

I also like where I grew up in northern Tanzania. I like the savanna and the high plateau. I like the wildlife. I have a hard time picking a city I like a lot.

Any places still on your list?

Maybe for my next lifetime. My wife wants to go to Antarctica. I don’t have time in this lifetime. It takes too long. I want to go to Tromso, in northern Norway. It’s where my ancestors are from. Very beautiful fjords and gullies. My ancestors were fishermen. I also want to go to Peru and Argentina and see the Andes.

What responsibility do you feel that western travelers have to the places that they visit?

If you can, go local, even for a day. It’s fine if you have a package tour, but spend at least one day a week doing something a little different than what’s on the rest of your itinerary. Spend some time in a local café. Get to know somebody. Go visit a school. It’s uncomfortable for people at first, but often people say that’s the most significant part of the trip.

I’ve studied this a bit. Budget tours actually bring more money into the local economy than a packaged tour. If you’re going to climb Kilimanjaro, maybe spend one day in a village somewhere. You don’t have to do that much. I think there is a consciousness there that you want to take time out to be with the people a little bit.

Not all of us are going to come back from a trip and start a foundation to fund education projects.

I hope not.

What do you recommend for the rest of us?

One of the things is to try to continue just one of your relationships that you made on your trip. Whether it’s a hotel worker or a guide, just keep in touch with somebody. I also think there are so many more travel companies that are giving five or 10 percent to local organizations.

And maybe what you saw was very beautiful, but you probably also saw some things that were not too pleasant. I think we shouldn’t try to bury them. We should talk about those things, whether it’s child labor or slavery or environmental degradation. The power of one is very powerful.

A big thrust of your education projects has been educating girls. We in the West consider it very laudable, but the people there don’t necessarily agree. Do you have any misgivings that you’re imposing your values on another culture?

I’m convinced that more of a focus on a girl’s education can really change society. But it’s not my idea. It’s what the people there say. What they tell me is, “We want two things. We don’t want our babies to die and we want our kids to go to school.” The number one way to reduce infant mortality is education and female literacy. But it has to be what they want, rather than what I want.

Our curriculum is very different from a normal curriculum. We have the elders come in and do storytelling. We have hygiene, sanitation and nutrition involved in our classes. We have set up micro-entrepreneurship, like poplar tree plantations and women’s vocational centers. It’s much broader than a normal school curriculum. The school kind of becomes a community center.

What difference have you seen these schools making outside the school walls?

Oh, it’s had a huge impact. Women are much more involved in the decision-making process. They’re involved in selling at the marketplace. The population curve is dramatically reduced after 15 years or 20 years, which I’m now seeing.

Also, the changes I see in Afghanistan and Pakistan are, women who have an education are much less likely to encourage their sons to get into violence or into terrorism. I’ve seen that happen. The Taliban’s primary recruiting ground is illiterate or impoverished society.

And here your books have been bestsellers, even though they’re on a topic that doesn’t usually make the bestseller list.

And here your books have been bestsellers, even though they’re on a topic that doesn’t usually make the bestseller list.

A part of it is the universal message of “Three Cups of Tea,” which means, take time out to get to know people. What the three cups of tea mean is, the first cup you’re a stranger, the second you’re a friend, the third you’re family. In the U.S., we have six-second sound bites, two-minute football drills, 30-minute power lunches. The one message is, take time out.

I also think it shows you the power of one person. I consider myself a very average person. I make a lot of mistakes. I have a lot of problems. But I’m also able to do quite a bit. I think anybody can do something if they put their heart and mind to it. I’ve met hundreds of people who are doing amazing things. I think part of the staying power of “Three Cups of Tea” is showing that one individual can make a difference, and that could be me. I think people identify through my bumblings and mistakes and failures, and I think they also identify with my successes.

I also think “Three Cups of Tea” appeals to a very wide group of people. It crosses ethnic and religious boundaries, liberals and conservatives. You’ve got Michelle Obama and Karl Rove pumping the same book. The Bush family. Antiwar activists. It’s also required reading in the military. People like to come together on some type of platform. It brings people of different ideologies together. They can both advocate for education.

Are there any travel writers who inspire you?

I love Rory Stewart’s “The Places in Between,” but it’s because he had a dog with him when he walked across Afghanistan. Eric Newby, who wrote “A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush.” Dervla Murphy, who wrote “Where the Indus is Young.” She traveled with her daughter. I’m interested when they have an animal or a kid, rather than just like hard-core travelers. Something a little bit different. I’m not so much into the solo epic stuff. That’s great, but it’s not really practical for most people.![]()