Journey to High Mountain

Travel Stories: In an e-book excerpt, Tara Austen Weaver finds a new home in rural Japan

12.13.11 | 12:36 PM ET

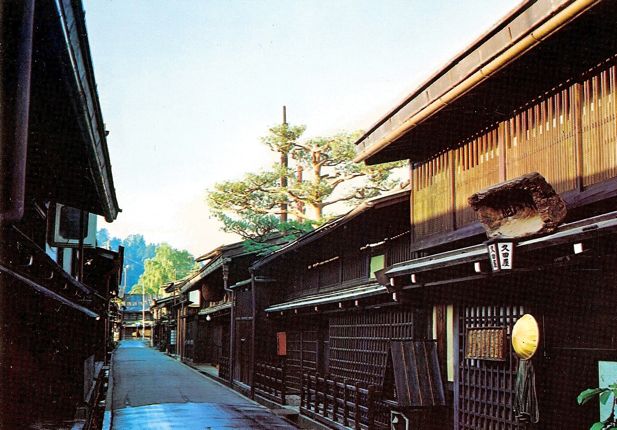

Takayama, Japan (Tara Austen Weaver)

Takayama, Japan (Tara Austen Weaver)The train to Takayama winds along the Shirakawa River and high into the mountains of central Japan. The water of the river flashes turquoise against white rocks, flowing and foaming over the stones. We pass small villages, houses of mud-colored walls with dark tiled roofs. An occasional temple flashes by, and carefully tended bushes I will learn later are tea plants. The train continues to climb higher and higher, up densely wooded mountains until it crests the final ridge and sweeps down into a wide valley filled with farmhouses and rice fields. This is where I’ve come to live.

Sitting in my train seat by the window, I am nervous. I am 21, just two months out of college, and not entirely sure what I am doing. I know my country is in recession, the job market is grim, and my art history degree qualifies me for exactly nothing. I like to travel and going to Japan—where simply speaking English is a marketable skill—seems smarter than trying to swim in a sea of eager graduates back home, the ink barely dry on our degrees. When friends of friends hear I’m interested in living in Japan, they invite me to stay with them in their home in the Japanese North Alps. The town is called Takayama, which means high mountain.

This is what the announcer calls over the loudspeaker as the train slows to a halt in the largest town we’ve seen since the trip started: Takayama, Takayama. I gather my bags and stumble onto the platform, feeling uncertain and awkward. Japan always makes me feel this way. I am too big for this country, too clumsy. Everything I do here attracts attention. The word in Japanese for foreigner means “outside person,” and that is what I feel like. An overly large, bumbling outsider. There is no way for me to fit in.

I am to be met by the mother of the family I will be staying with. I don’t know what she looks like. I know only her name—Kaoru—a word whose pronunciation leaves me mystified (ka-o-ru). I assume she will recognize me, the lone foreigner on the train. When a tall slender woman in her 50s with long hair approaches me and says my name, I smile, bow, and follow her as she walks away from the train station.

Without much conversation Kaoru-san leads me down side streets and over a river that flows through the center of town. Three small bridges cross the river: one painted an orangey red, another green, the last one made of stone. In America they would be pedestrian bridges—they’re that narrow—but here they are for car traffic, vehicles much smaller than I am used to. The tiny delivery vans remind me of toy cars. They look like breadboxes on wheels.

At the far side of the bridge we turn down an even narrower street and enter a coffee shop. Kaoru-san orders a peach soda for me and, in a mix of Japanese and halting English, tells me I will be her American daughter. I don’t know how to respond to such an announcement. I barely remember my one semester of college Japanese, four years earlier, but I am sure it did not cover spontaneous adoptions. Again, I smile and bow. “Domo arigato gozaimasu,” I say. Thank you very much.

When we leave the coffee shop, Kaoru-san leads me through a rabbit warren of small streets lined with traditional low houses made of wood. I can tell this part of town is old. The windows are covered with wooden slats and there is a narrow stone ditch filled with running water on either side of the street—a method of wastewater disposal, presumably, from an era before plumbing. At each entrance, planks of wood bridge this small gap and lead to the door.

Kaoru-san walks up to one of these houses and slides the wood and glass door open. “Tadaima,” she says loudly, as she walks into the paved entryway. I know this word. It means, “I have come home,” and is used when a family member returns from wherever they have been. I repeat it quietly after her as I too enter the house. Tadaima: I have come home.

Though I have been in Japanese homes before, Kaoru-san’s house is the most traditional I have ever seen. Light filters dimly from a high window onto tatami mat floors made of straw. Brush calligraphy and woodblock prints hang on the walls. The wooden posts have been worn smooth and shiny from generations of hands. It smells like years of incense and old newspaper. I feel as if I’ve gone back in time.

Kaoru-san shows me my room—tucked under the eaves and overlooking the small street. To reach it I climb up a wooden chest of drawers carved into the shape of a small staircase. I’ve seen such things in Asian antique shops; I know they fetch a high price from collectors. Kaoru-san couldn’t possibly sell hers, however. There would be no other way to reach the second story of her house.

That night at dinner I meet the rest of the family—an 11-year-old daughter, Mai-chan, who smiles shyly, and the father of the family, Oto-san, who speaks in short fast bursts I cannot follow. I cannot follow much. My language skills are no match for real conversation. I can say my name. I can ask to use the bathroom and for directions to the train station. I can say please and thank you and tell you dinner was delicious. I can smile and I can bow. So I do, a lot.

Our meal that night is oden—a Japanese stew of fishcakes and vegetables cooked in broth, popular in the winter. It is served family-style: one large steaming pot in the middle of the table from which we all help ourselves. The slippery fish cakes elude my chopsticks, falling back into the pot every time I try to grasp them. I thought I knew how to use chopsticks, but oden makes me look like a beginner.

Kaoru-san has given me wooden chopsticks with grooves carved around the tip of the shaft. I wonder if these are special chopsticks. Perhaps they are the culinary equivalent of training wheels, given to children and helpless foreigners.

After dinner I hope I will be allowed to go to bed. I’ve been traveling for days and feel exhausted and overwhelmed. I want nothing more than to crawl into bed and pull the covers over my head. But there is one more thing I must do before I sleep. Kaoru-san looks at me and says a word I recognize: Ofuro. It’s time for my bath.

The bathhouse is located behind the home—reached via a stone walkway that crosses a small garden. The bathhouse door leads into a changing room where I remove my slippers and clothes, sliding open the final door into the steamy bathing room. There are wooden slats raised above the cement floor. To the right is a small but deep metal tub. On the far wall I see a water faucet, a wooden stool, and a bucket. I’ve been in Japanese baths before. I know what to do.

I pull out the stool and sit down, turning the faucet handle on. The bucket fills with hot water and I pour it over my shoulders and back, rinsing away the day’s travel grime. I quickly begin to scrub with soap, lathering myself completely before washing off again, pouring buckets and buckets of hot water over me. The steaming water cascading over my shoulders and back feels sacred—a ritual or sacrament. I feel more than clean, I feel cleansed. The soapy water drains through a grated hole in the floor. Only when I am entirely rinsed do I move to the tub.

The bath is scalding, painful at first, mellowing to a deep intense heat. I lower myself into the water slowly. The tub is short and deep. I cannot stretch my legs fully, but the water comes to my neck, entirely submerging my body and shoulders. A small cloth bag filled with fresh pine needles floats on the surface, scenting the water and reminding me that we are in the mountains. I lean back and feel the knots in my shoulders loosen and slip away. The hot water unravels the strain and fear of navigating this new world and I succumb entirely to the ofuro. When I emerge I am bright pink, radiating heat, more relaxed than I thought possible.

That night I sleep on a small pillow stuffed with buckwheat hulls, tucked in bed under the eaves. I hear occasional footsteps on the street below my window, though the glass is frosted and wooden slats keep me from being able to see out. I find a pinprick of light on my pillow. This I trace back to a small hole in the wall where the plaster has fallen away, allowing the streetlamp from outside to shine through. These walls, I realize, are older than my country.

I wonder what I’m doing here, so very far from home.![]()

This is an excerpt from Tales from High Mountain, an e-book benefiting ongoing rebuilding efforts in Japan from the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Purchase the Kindle version or buy a PDF.