The Speed of Rancho Santa Inés

Travel Stories: The saying goes: Bad roads, good people. Good roads, bad people. On a sleepy Mexican ranch, C.M. Mayo finds out what the Transpeninsular Highway brought to one stretch of Baja California.

10.18.06 | 4:05 PM ET

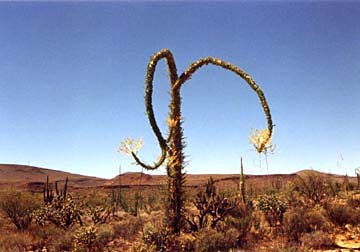

Photo by C.M. Mayo.

Photo by C.M. Mayo.At Rancho Santa Inés there were no mules for our trip to Mission Santa María Cabukakaamung. The ranch hands had looked, but the mules had wandered through the desert too far in search of forage. Literally, they could not find them.

Nearing sundown, Alice and I sat at a picnic table under a thatched awning while the cook made scrambled eggs with machaca for our supper. A pot of beans bubbled on the stove. The smell of the cooking wafted out from the open kitchen. The wall by the counter was plastered with bumper stickers: I’D RATHER BE IN BAJA read one; KILL A BIKER… GO TO JAIL. Several were from the Baja 1000 off-road race, which used the ranch as a pit stop. Alice and I were the only guests tonight.

A small white poodle-like mutt nuzzled our legs. Palomito was his name, the cook said. A Calico cat slunk up as well, meowing loudly. And her name? “Gato,” she said. Cat. She broke out laughing at me, that I would ask.

A capable-looking woman with short hair graying at the roots, her name was Matilda Valdez. She sat with us at the picnic table while we ate. She’d lived here for 24 years, she said. No, she’d never been out to the mission. Her husband didn’t like her to leave the ranch house. “He says, you’re a housewife, so this is where you belong.”

As we spoke, the light faded. The ranch did not have electricity; Matilda switched on a small gas lamp.

When we were finished eating, she sighed and rested her chin in her hands. “I would like to go to the United States,” she said. “I like the style of life there. But I’m too old now, I wouldn’t know how to live there. What would I do?”

In the morning, for breakfast we ate eggs and machaca again; it was all they had. Matilda shooed away the cat, then went back into the kitchen where she lingered like a shadow, washing dishes. At 8 a.m., it was already broiling hot. And strangely quiet—there were no chickens here, no goats. I watched Palomito sniff around our jeep, lifting his leg on each tire, and I thought of all the dogs that had marked them over the past several days.

“Doggie bush mail,” I said.

Alice sipped her coffee. “More like message in a bottle.”

Matilda’s husband was named Oscar Valdez. Trim and tough-looking, he had a pencil-thin mustache and eyes that peered out hard and slit-like from beneath a crisply molded white cowboy hat. On his belt he wore a turquoise-encrusted silver buckle.

I still had my hopes of getting to Mission Santa María Cabujakaamung. Was the road really impassable?

“Es malo,” it’s bad, Oscar said, “muy malo.” It used to be better; he’d built it himself, together with his father and cousins in the sixties. But it hadn’t been kept up, chubascos had washed out large sections. We could hike to the mission and camp overnight, he suggested.

We’d lost that time, I explained. Alice had to catch her flight from Loreto, to be back at work.

He swung a leg over the bench of the picnic table. Palomito leapt up and laid his chin on Oscar’s lap. The mission was just ruins, he said, not much to see. But he had a picture in a book from the 1920s that showed the adobe walls still standing. Gently, he patted the little dog behind its ears.

A German film crew recently had come to make a movie about the mission. “They filmed what happened two hundred years ago when they sent the priests home. Then some others came and they took the Indians to Alta California. They put them all in chains. The actors wore soldiers’ uniforms from then, very different from today!” He raised his eyebrows and smiled, and shook his head. “They had a book and they were reading the history from that book, two hundred years ago! Oh, how can they know about this place and I live here!”

Oscar, I realized, was much more interesting than some old lumps of adobe.

“¡Todo rápido!” Everything goes fast now, Oscar said, fast! He wanted to tell me how things were before the highway was built. Before, he said, a car might pass by once a week, maybe once every 10 days. “You could lie down and go to sleep in the middle of the road and nothing would happen to you!”

He threw back his head and roared.

Oscar may have looked slick—the big white cowboy hat, the flashy belt buckle—but he hadn’t owned a pair of shoes, he said, until he was 14 years old. One day, a mounted salesman arrived with his burro train from the sierras, selling shoes. Oscar had a bitch he liked, so they made a trade. “She was a good dog,” he said as he stroked Palomito’s curly white scruff. “But I really wanted those shoes. My first shoes.”

When they needed to go to Ensenada they went on burro. “It took us two or three weeks. And sometimes I would go to Santa Rosalía. I would eat at the ranches on the way for free.”

There was no doctor. “You would ask yourself, am I sick? And you’d have to say, no, I’m not sick. Because if you are, well,”—he pointed to the yard—“there’s the cemetery!”

He leaned over to the sugar bowl and raised a spoonful. “My father didn’t know sugar until he was sixteen,” he said, letting the sugar cascade back into the bowl. “‘How can this be sweet?’ my father said. ‘It looks like salt!’ He only knew honey.”

“And bullets…” he said. “We only had a very few,” poquitas, poquitas. “They were very expensive, my father would keep them wrapped very carefully in a handkerchief. We had to save our bullets for deer, because that was food. If you were going to shoot a deer, you’d better aim well, kill it on the first try. You couldn’t shoot coyotes or mountain lions, nothing like that.” He laughed scornfully. “Not like today. Today bullets are cheap, they just go around shooting at whatever.”

I mentioned the bullet hole I’d seen on the “golden spike” monument down the road at San Ignacito.

“I was on the road crew,” he said proudly. He’d worked as a tractor driver for the local section.

He’d been there at San Ignacito when the road crews met. “There was a big party. They gave us lots of barbecue, and trailers and trailers full of beer.” The governor arrived with newspaper reporters to cover the ceremony. “There were a thousand people!” Oscar said, eyes wide. “I had never seen so many people in one place at the same time.” That was in 1973.

The highway opened vistas for Oscar. Working on the road crew, he met people from other parts of Mexico. And instead of herding goats, he was able now to make a living from tourism. Every week Rancho Santa Inés had a handful of guests, not just Americans and Mexicans, but Italians, Frenchmen, Germans, Canadians, even Japanese.

Now there were a lot of people passing through on the highway, Oscar said, all kinds of people. There had been a number of hold-ups, several bad accidents. Like most Baja Californians, Oscar was wary of mainland Mexicans. Some of them were good people, he allowed, but they had different customs. Many were drunks. Some of them would fight with guns and knives. “Here in Baja California,” he said sternly, “we fight with our hands.”

Bad roads, good people, goes the saying, good roads, bad people.

Now there was the hotel, the gas station, the trailer park. And added to all that, as of three years ago, they had TV, Televisa from Mexico City.

“Everything goes so fast!” Oscar said again. His eyes nearly disappeared in the creases of his grin. “Fast!”![]()