The Sound of Sunshine

Travel Stories: Frank Bures was working for a boss he didn't like, spending too much time alone. It was a dark time. He found light in the bright, poignant music he first encountered in Africa: soukous.

07.03.06 | 10:18 AM ET

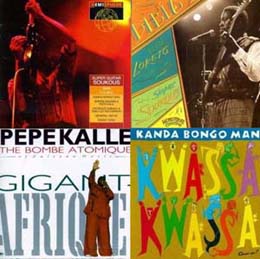

It was a dark time, and looking back on it now, sometimes I think the only thing that saved me was soukous, a sound I had brought home with me from Tanzania. On bad days in that room, when I hadn’t seen sunlight for what felt like days, I would put my headphones on, put on Dalle Kimoko, or Kanda Bongo Man, or Pepe Kalle and be lifted up to a place where the sun was shining, a place that was green, a place where people were laughing. It was a place I knew well—a place that was hard to live in, to survive in, but where, for some reason I could never quite understand, something had not died. It was only when I put those headphones on that I realized what that was. It was a feeling I had known a long time ago. The best English word I can think of for it is “joy.”

Soukous is that feeling rendered into sound.

It is strange how it came into being—one of those bizarre creatures of globalization. It started in the 1930s in the deepest, darkest Congo, where they were spinning records: Sexteto Habanero, Trio Matamoros, the Havana Casino Orchestra. As world trade started to accelerate, the greats of Cuban rumba found themselves booming over the nightclubs of Kinshasa and Brazzaville. The sounds from the new world were the sometimes quick, sometimes slow beat rhythms known as rumba. Those sounds struck a chord in Congo, since many of its elements had been imported to Cuba on the slave ships. When they came back, they were like old family—long lost brothers that had grown up and were being welcomed home.

In the 1940s, Greek traders in Kinshasa started importing recording equipment and setting up studios around the city. They pressed this new sound into new records, and launched a new genre that would give the world sounds like it had never heard.

Before long, soukous started to take off, departing from its Cuban roots, and within a few decades it had become something else entirely. It was faster. It was more aggressive. It was more celebratory. The crescendo had built up into the feverish dance beat that is soukous, one of the most powerful sounds of the 20th century.

But there was something else, too, under the layers of rhythm and guitar, something more complex that was not just dance music. It was something Susan Orlean noted in her essay on an African record shop in Paris. “You can dance for hours and hours to soukous,” she said, “But it is also strangely, ineffably poignant. Even the biggest, brassiest soukous songs have a wistful undercurrent, the sound of something longed for or lost.”

There is plenty to be longed for and lost in Africa, as there is among the African expatriates in Paris, and this is exactly what I love most about soukous: It refuses to stop dancing and laughing in spite of all that.

But these days, soukous itself is becoming something to be longed for and lost. It was still going strong when I lived in East Africa in the 1990s. The Soukous Stars were still shining. Franco was dead, but still alive on tinny tape players on every street corner. Yondo Sister was grinding her hips in sexy videos on every video bus that crossed the continent. But the end was coming. Rap was already knocking at its door, and today it has walked in and taken over the whole room, sometimes mingling, sometimes dancing with soukous. Already there have been soukous revivals, and I would not be surprised if something else just as vibrant was born from it.

Still, the sound carries on, and remains one of the great treasures of the music of the world, something that couldn’t have emerged from any other place or time. It is the perfect encapsulation of something, maybe the sunshine and the laughter that can get you through just about anything.

One day at the bookstore, I was talking to John, my coworker, who asked me what I was listening to. I shrugged and told him, not expecting anyone to know what soukous was. But John did, and confessed that he loved it too, a fellow castaway on the sunny island of soukous.

I lent him one of my best CDs, a French label I had stumbled across at a West Coast record store. There were none of the big soukous names on it. It was just some guys who made a record and probably ended up back on the farm.

But here were their sounds—the sweet, driving bass guitar, the lovely Lingala lyrics, the mesmerizing rhythms that, once they hooked you would never let go. It was pure soukous. It was pure magic—the kind of music that can shine into the darkest corner of your soul.

Now, just about the time I gave John my best soukous CD, he started taking some new medications for back pain. He took the CD home, put it on and just started dancing. And dancing. And dancing. He spent the whole night listening to that CD over and over and over, spinning, in circles. The music played him like an instrument. It lit him up from the inside out.

Later, seriously sleep deprived, John went to his doctor and told him what had happened, and that he thought the new medicine was making him manic.

But the doctor just looked at him and told him that such a thing was unheard of in the history of medicine.

In other words, it wasn’t the medicine at all.

It was the soukous.![]()