The Art of the Deal

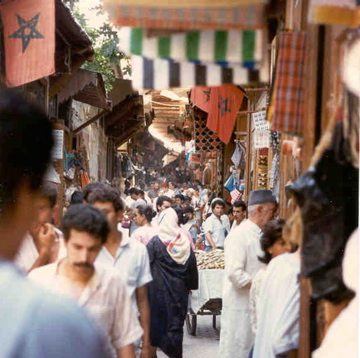

Travel Stories: In Marrakesh, Morocco, Peter Wortsman bargains for goods with the city's savviest shopkeeers. For him, the give-and-take is not just about the money.

11.10.06 | 1:15 PM ET

Photo by Peter Wortsman.

Photo by Peter Wortsman.The day my wife and I arrived in Marrakesh, Morocco, the thermometer topped 105 degrees Farenheit in the shade. We unwittingly paid three times the going rate for a cab from the airport to our hotel, we rented a rattletrap at what we naively thought was a discount, and proceeded to have two flats on purportedly “brand new” tires. Assailed by hordes of adolescent would-be guides, we were at a total loss until a canny stranger stepped out of the crowd, informed the kids that we already had a guide and chased them away. Mustafa, with whom we were now “affiliated,” like livestock to a shepherd, led us back to our hotel where we resolved to leave the country immediately. Fortunately, we slept on that decision.

It hit me suddenly the following day at the tanner’s stall in the souk, the outdoor market where Mustafa had taken us “just to please our eyes.” Pointing to a cream-colored camel’s leather footstool at which we’d glanced with vague interest, the tanner scribbled a figure in the upper left corner of a checkered pad and handed it to me. The price was outrageously high. One moment I was livid at being taken for a fool, the next moment a light went on in the convoluted Casbah of my brain. I scribbled a ridiculously low figure in the bottom right corner. The tanner scowled.

“Look,” I said, pointing to my wife, “that’s my queen! I’m the king. Now let’s sit down and play chess!”

His scowl immediately inverted into a smile. I’d understood that it was all a game. We passed the pad back and forth, and I came away a half hour later, camel’s leather footstool in hand, with the tanner’s grudging admiration for a match well played.

Most Americans accustomed to shopping malls find bargaining an embarrassment, something seedy that your great aunt Sadie or uncle Silvester did while squeezing the fruit or feeling the material. We expect our commodities cellophane-wrapped and sticker-priced, and seldom say more to the person who sells it than please, thanks or charge it.

But in Morocco, as in much of the rest of the world, bargaining is a way of life. You bargain over everything from marriage dowries to speeding tickets. The taxis have no meters but passenger and driver have mouths. And though car rental agencies, native and international, list their rates in orderly columns in glossy brochures, just like back in the States, the actual price you end up paying fluctuates with each transaction. Practiced with a varying degree of expertise by every Moroccan man, woman and child, bargaining tests the mettle, sounds your character, pits will against will and wile against wile, and also, incidentally, can be a lot of fun.

The uninitiated tourist has two choices: he can look on and let himself be milked, or learn the rules of the game and join in, responding with the same blend of blarney, charm, cunning, savvy and seduction.

“Hello, Ali Baba!” the tailor from Tangier, the goldsmith from Fez, the tanner from Marrakesh all greeted us with glistening teeth and a golden grin. “Come look! Just to satisfy the eyes!” And before we could even think of straying to the competition, octopus arms were sweeping us in. The decor was authentic Oriental, the scenario seldom varied.

“Be seated, my friend!” our host always insisted, pulling out a pair of wobbly stools or stuffed leather cushions. Steaming glasses of mint tea appeared on knee-high round metal tables. Smiles abounded and sincere words of welcome ricocheted against false teeth. What followed was pure burlesque, vintage entertainment, if taken with the right attitude. Depending on the nature of his ware, the proprietor pulled out a genuine “antique” dagger and tested its tempered blade on a hair plucked from his assistant’s pate; or spread an ornately patterned rug at our feet and swore (with a carnival grin) you could fly it all the way home and never get airsick.

Take my tangle with the tailor from Tangier as a case in point. “Such a lovely lady!” he complimented my wife, coaxing her to try on a pair of “pantalons climatisÃ(c)s” (air-conditioned harem pants), span a necklace round her neck, and slip a pair of gold embroidered slippers on her “alabaster” feet. Then once again complimenting the beauty of “la gazelle” with renewed enthusiasm, he turned to “le gazeau,” the befuddled buck, and sprung an astronomical price. But I was ready.

Custom demanded he ask at least three times what he hoped to get (more in the case of Americans, known for their gullibility and cash flow). No Moroccan would ever take such a first quote seriously, but tourists are always worth a try.

I replied with the proper response: a brow raised in stunned disbelief, signifying in silent pantomime, You gotta be kidding!

The tailor gallantly deferred to my objections with an obsequious palm. It was my turn now to present a counter-offer, contrapuntally as preposterously low as his was high, a tenth of what I might agree to pay. Pretending disinterest, I remarked that though the garments in question were indeed attractive—Never offend the merchant or his merchandise outright!—I’d seen their equal elsewhere for less.

True to his prescribed role, the tailor wrung his hands and swore I was out to ruin him, to drive his innocent children out begging in the street. And furthermore, “Monsieur surely cannot recognize quality when he sees it! Feel this leather—genuine camel! Touch this cloth—100 percent silk! Surely Monsieur is jesting, but to prove that I too have a sense of humor,” he laughed, rapidly regaining his lapsed composure, “I will give you this fabulous garment, hand sewn and embroidered by the King’s own personal tailor, for the price of a pair of jeans!” (Note: Levi’s cost a king’s ransom in the Third World.)

Since he now had come down a feather, I too, had to give a hair. And so the bargaining continued, offer vs. counter-offer, until my wife and I had sipped our last drop of tea, no refills forthcoming, and I detected a flutter of impatience on the tailor’s lips.

This was the moment of truth, or rather, the moment immediately preceding the moment of truth, an essential distinction every poker player will recognize as the bluff that ups the ante.

“Very well, my friend,” the tailor grasped my hand in feigned defeat. “You play a hard bargain, Monsieur, but I will let you have the whole lot, necklace, dress and slippers for 1,000 Dirhams!”

“Sorry,” I shook my head, sighed politely, grasped the hand of my “gazelle,” and made for the door. “I can give you 500 Dirhams and not a Dirham more, or else I won’t have the money left for dinner!”

The tailor, of course, refused, and as we exited his premises we cast our sights on the stall next door, waiting for one of two things to happen. Muttering curses under his breath, he would either let us go (an unlikely eventuality), or drag us back in. For now and only now, like a luscious date begging to be plucked from the sagging palm, the deal was ripe.

Transaction completed, the tailor and I shook hands. Something more than goods and money were exchanged: an acknowledgment of mutual respect, the satisfaction of a game well played, with the implicit possibility of a re-match, Allah-willing, tomorrow or another day.![]()