The Joy of Steam

Travel Stories: Tony Perrottet went for a simple scrub down at the oldest bath house in Istanbul and discovered a link to the ancient Roman Empire

11.03.05 | 10:29 PM ET

Photo by Kate Milford.

Photo by Kate Milford.Sex, wine and the baths may ruin our bodies, but they make life worth living.—Ancient Roman gravestone

Arriving in the Sultanahmet district of Istanbul, built atop the ruins of the Greek city of Byzantium and the Roman capital of Constantinople, I already felt like I’d traveled halfway back in time to the ancient world. Then, in tea houses all over the city, I found dog-eared leaflets advertising the pleasures of Cagaloglu Hamam, the city’s oldest bath house:

HAVE YOU EVER BEEN IN A TURKISH BATH? IF YOU HAVEN’T, YOU’VE MISSED ONE OF LIFE’S GREAT EXPERIENCES AND NEVER BEEN CLEAN!

The sales pitch added that Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, the composer Franz Liszt, Florence Nightingale and Cameron Diaz had all enjoyed steam baths here. No less than 138 films had been shot within the hamam’s walls, and innumerable newspaper stories written:

THE PRESS HAS MUCH PRAISED THIS BATHING HABIT!

How could I resist? For anyone interested in how antiquity has survived to the modern day, a visit to a Turkish bath is essential: the Islamic hamam is possibly the most striking link we have to a key social practice of the Greco-Roman world—especially for a traveler.

Two thousand years ago, if you were visiting any city in the Roman Empire, you would be woken by the melodious bass of a copper gong resounding through the streets at dawn, announcing the opening of the thermae, or heated public baths—a sound, Cicero rhapsodized, that was sweeter than the voices of all the philosophers in Athens. These ancient baths were far more than mere palaces of cleanliness: They were the Western world’s first true entertainment complexes, combining the facilities of modern gyms, massage parlors, restaurants, community centers and tourist information offices. They were the ideal place to meet locals or get hot travel tips: In those palatial halls, citizens of all classes lolled by the pools, met their friends, played ball games, relaxed, flirted, drank wine and even had elegant candle-lit dinners. And like nightclubs or gyms today, a city’s baths were unofficially graded: Some were chic, others déclassé; some were expensive, others cost only a copper; some were magnificently designed, as large as cathedrals, decorated with enormous mosaics of Neptune and his dolphins.

In short, a visit to the baths was the ideal way to enter the social life of a strange city.

Modern Turkey offers a unique connection to this ancient tradition. Two thousand years ago it was the Roman province of Asia Minor, and it’s the only place in the Mediterranean where the historical line back to the thermae is unbroken. In Western Europe, the habit of public bathing did not survive the collapse of the Roman Empire. During the Middle Ages, good Christians became ashamed of their bodies, and showed their repugnance of earthly matters by refusing to wash, remaining smelly, squalid and flea-bitten until the late 19th century. But in the Eastern half of the Empire, soon known as Byzantium, the great Roman baths stayed open, and were even more popular after the Ottoman Empire conquered Turkey in the 15th century A.D. Islam adhered to the ancient obsession with personal cleanliness, as well as the Greco-Roman tradition of bathing in public. Of course, there were some big changes, too: Total nudity was forbidden under Islam; men wore loincloths, and women were provided with separate baths. But the connection is still powerful. In modern Turkey, many bath houses even still stand on the original classical sites. In fact, the very name “Turkish bath” was given by British visitors to Constantinople in the 16th century, who saw the ancient Roman thermae still in operation and incorrectly assumed they were an Ottoman invention.

Today, there are over 60 baths still officially registered in Istanbul. Sadly, these last hamams are under siege, as Turks in the big city increasingly prefer Western-style bathing in the privacy of their homes. Young Turks find steam rooms decidedly outré—several warned me that they were dens of disease and foot-rot, frequented only by country bumpkins, geriatrics and male prostitutes. And yet the venerable institution staggers on.

Visiting Istanbul was obviously my big chance to experience this ancient travelers’ tradition. Still, I found myself delaying: The embarrassing fact was, I’d never had a massage, let alone visited an actual bath house back home in New York. But by the time I’d picked up my tenth leaflet singing the praises of Cagaloglu Hamam, I finally decided to give this famous washing experience a shot. After all, it was reputed to be the most palatial bath house extant in all Turkey, and has been in continuous operation at least since 1741. An English photographer I was traveling with reluctantly agreed to join me. I wasn’t sure if Nik was a wise companion: Even more than most of us self-conscious Westerners, he viewed public bath houses as deeply seedy places, and held an unshakable conviction, apparently gleaned from “Lawrence of Arabia” and “Midnight Express,” that Turks were polymorphously perverse.

But we grabbed our towels and headed off valiantly into the night, on a modest expedition into the damp underbelly of antiquity.

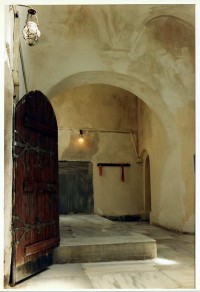

Admittedly, my first vision of Cagaloglu’s exterior did give me pause. In a noisy side street, a sunken entrance displayed a frayed sign in four languages, along with a string of bleached photographs showing a parade of rather louche-looking semi-celebrities who had sweated it up here in the 1960s.

“Are we feeling confident in our masculinity?” Nik mused.

Inside, the once-palatial entryway looked grimier than 260 years of continuous use could possibly account for. The courtyard of marble and mahogany must once have been an uplifting sight; now, its latticework was dark and dimly lit. The elegant fountain was dry, and half a dozen cockroaches lay belly up in one corner, alongside an empty Evian bottle.

An old man at the desk woke from a deep slumber and blinked at us in surprise.

“Are you open tonight?” I asked.

He shuffled some papers. “Why not?” He raised a hand, and an attendant in a bright orange loincloth slouched like a tubercular genie from the shadows.

Ahmed the masseuse was thin and wiry, with sunken eyes, and decidedly yellow around the gills; he appeared to be coated from head to foot in nicotine. He stood solicitously by as we made the financial arrangements. I passed on the obscure “Sultan Service” and agreed to the standard “bath and massage.” Nik cautiously paid up for bath-only.

“Ahmed’s not really my type,” he helpfully explained.

At the sight of the change rooms, dank little vinyl-covered cubicles, Nik was all for turning back, but I had a sense of duty. This was my direct link to the Romans—although it occurred to me, and not for the last time, that a lot can change in 2,000 years.

Back in the fourth century A.D, when Constantinople was the Empire’s jewel, the atmosphere at its bath houses was not unlike a crowded Mediterranean beach in summer today. The noise was infernal. All around, merry-makers were exercising, splashing water and playing hand ball; food vendors bellowed from their podiums, and professional hair-pluckers induced shrieks of pain in their clients that rose well above the general din. Petty thieves worked the crowd, rifling through belongings while the owners swam or slept, while the wealthy trawled the steam rooms handing out banquet invitations to potential sexual partners.

It’s not surprising that the Christians were horrified by pagan behavior at these places: Bathing, sex and food were the Holy Trinity of the Roman good life, and the co-ed thermae encouraged all three. Romans learned to parade naked in the heated pools—those who hid themselves were ridiculed. The poet Martial was affronted when one young woman refused to share a bath with him; he assumed she was trying to hide some dreadful physical defect. Even worse, from the Christian point of view, were the male-only baths, since homosexuality was openly accepted in Roman society, at least between teenage boys and their adult “mentors.”

Erotic foreplay continued all the way from the steam rooms to the baths’ bars and restaurants, where flushed lovers—or wealthy women and their Adonis-like young slaves—could eye one another over a jug of chilled wine and figs. Private rooms were provided for consummation, decorated with lewd frescoes. Special magical spells were devised to incite romance at the baths. (Some were a little bizarre: “To attract a lover at the thermae: First, rub a tick from a dead dog on your genitals…” Another spell needed to be written in the blood of a donkey on a papyrus sheet, which should then be glued onto the ceiling of the vapor room—“you will marvel at the results,” the author promised). As one graffito in a Herculaneum bath crowed: “We, Appelles the Mouse and his brother Dexter, lovingly fucked two women twice.”

Soon Nik and I were ushered from the fetid changing booths to the first steam room, where a wall of hot, stale air hit like the exhalations of a demonic laundry.

I had to admit that the domed vault of Cagaloglu was impressively cathedral-like—there were even Corinthian columns harking back to the Roman style—and shafts of white light glowed through thick swirling mist, descending from holes in the domed ceiling and ricocheting off the polished marble interior. But a sullen lethargy pervaded the air. About a dozen sallow customers in loincloths lolled about in the shadows, groaning ominously, as if they were drunk. A couple of guys looked as if they hadn’t left this room for years.

I lay for a while on a hot stone block, before Ahmed the masseuse emerged again from the mist like a zombie in the Louisiana bayous. Without fanfare, he got to work for the skin-scraping, wielding an abrasive mitten—the modern descendent of the ancient strigile, a curved metal instrument that removed dirt, sand, sweat and exfoliated skin, all mixed up in the olive oil that was used throughout antiquity as a soap; this nauseating mixture would then be flicked by the ancient masseurs onto a nearby wall. Ahmed kept swiping languidly, as if he was brushing a longhaired dachshund, while the scent of tobacco mingled with the perfume of foot odor wafting from the floor. Abruptly, he paused and brought his head next to my ear.

“You want—special service?” Ahmed breathed.

“No!” I jumped. “Why? What is it?”

“Shampoo massage,” he confided, pointing to a running fountain. I could get a real massage—but I had to pay top dollar.

“Going for a little rough trade?” Nik asked from the nearby mat, after I’d agreed.

Ahmed looked at him archly. “You would like special massage also?”

“Not me,” Nik put up his hands defensively. “I’m strictly self-service.”

We have a modest insight into how a Roman traveler might have behaved at this stage of a bath house visit, thanks to the fragmentary survival of a bilingual Greek-Latin phrase book. Like any modern Berlitz guide, its vocabulary list is complemented by a colloquia, or “dialogue scene.” The Roman speaker arrives with a sizeable party of friends and imperiously chooses a slave attendant: Follow us. Yes, you. Look after our clothes carefully, and find us a place.

Let me have a word to the perfumier. Hello, Julius. Give me incense and myrrh for 20 people. No, no, best quality.

Now, boy, undo my shoes. Take my clothes. Oil me.

All right, let’s go in.

A few minutes into my modern “special massage,” I could have done with a language phrase book myself. Specifically, what was the Turkish for: My spleen is about to burst.

As my unaccustomed flesh was torn and chopped by Ahmed’s tobacco-cured fingers, I tried to distract myself, yet again, with the knowledge that I was part of a tradition dating back to Cicero and Caesar. But I had to admit that only the most superficial elements of the Roman bath habit had really survived.

The formal structure of a visit may be the same—the ancients went from steam rooms to washing rooms to massage rooms—but the fact is, for the Romans, these had really only been excuses for a visit to the thermae. It was the peripheral circus—the people-watching, the chance meetings, the dinner invitations, the ball games, the snacks, the gossip, the pick-up artists, the vendors and beauticians—that made the baths so addictive in antiquity. Today, thanks to the inroads of Western bathing habits in Istanbul, convincing many Turks to shower at home, there has been a quantum leap from that original social purpose.

In one last forlorn echo of Roman times, Cagaloglu did maintain a restaurant in its shadowy foyer for a post-massage treat—although all it apparently stocked was moist pistachios instead of fresh fish, venison, blood sausage and pig’s trotters.

When I staggered out of the steam room, Nik was the only one there, quietly chugging down a warm beer. He motioned to a bench. “Take a seat—if it’s not too painful, that is.”

As I was recovering, a trio of pale Danish visitors wandered in, looking around with some confusion, and then were ushered into the changing rooms. Most things may have changed in the baths since Roman times, I thought, but at least the travelers were still hopeful: It was only tourists to Istanbul, really, who were keeping Cagaloglu’s doors open.

You could call it the last vestige of ancient tradition—which was something, I supposed.![]()