Welcome to Bizarroland

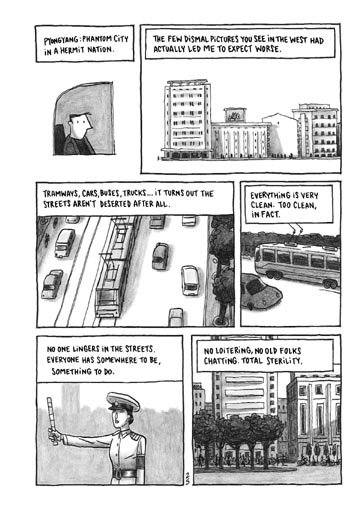

Travel Books: Guy Delisle spent two months working in the strangest and most reclusive country in the world, North Korea. The result was his new graphic novel/travelogue, "Pyongyang," which Frank Bures finds insightful, funny and, at times, touching.

09.21.05 | 7:49 PM ET

The Ryugyong Hotel was designed to host part of the 1988 Olympics, and would have been the largest hotel in Asia, a real triumph of the will to build hotels. But it wasn’t finished and was abandoned the following year. It has been there ever since, an omnipresent reminder of just how spectacular failure can be.

Guy Delisle, a French-Canadian cartoonist, sketched the behemoth in his new graphic novel-cum-travelogue, “Pyongyang.” In 2001, he lived in the city for two months while he oversaw subcontracted cartoon drawing for a French company. Pyongyang is his fourth graphic novel, including one about his travels to China, but his first in English. It also joins a handful of other graphic travelogues that have cropped up in recent years, like Josh Neufeld’s A Few Perfect Hours, Craig Thompson’s Carnet De Voyagen, and Ted Rall’s To Afghanistan and Back. But Pyongyang is the first such account about how things look inside of one of the most secretive and iron-fisted regimes on the planet.

The picture he draws is almost impossible to believe: a country where years are counted from the conception (not birth) of Kim il-Sung, where food aid is divided between “useful population” and “useless population,” where radios blare propaganda in every room, where gruesome stories of WWII and the Korean War replay on an endless loop, where the best store in town offers one shoe style in two colors, where people get genuinely teary-eyed about the “Dear Leader,” and-most stunning of all—where people seem to actually believe everything they’re told.

Needless to say, it was a long two months for Delisle, who was staying in the only lit floor of a 47-story hotel (one of three for foreigners), ate in empty restaurants with wet tablecloths, and was forbidden to go anywhere without a “guide.” These helpers proved utterly humorless and unflagging in their allegiance to the regime, but most of all in their devotion to the guidance and wisdom of Kim Jong-il.

This is perhaps the most disturbing aspect of life in North Korea today: the personality cult that seems to be at the heart of life there. Everything revolves around the twin stars of Kim il-Sung (deceased in 1994, but still president) and his son, Kim Jong-il, whose feats are expounded upon everywhere (he published 1,200 works as a student, scored 11 holes-in-one in his first golf game, and was born beneath a double rainbow and a shining star).

Few travelers have made it to North Korea, though there have been a few openings for South Koreans who want to stay at select mountain resorts. But Delisle and a handful of expatriate workers have been allowed in, and their accounts (along with those of refugees) make up almost all our knowledge of the country.

It isn’t much. Mostly, North Korea remains a puzzle and a paradox. How could any country still be completely offline? How could such utter Stalinist distopianism survive till now? And how can people buy the crap they’re fed?

Delisle asks questions but gets few answers. His guides and co-workers never crack, always sing along with the anthems on the radio, always issue heartfelt support for the compassionate leadership of Kim Jong-il.

There are a few hints that all is not as it seems: the stony silence when Delisle asks where a certain animator had gone; a man outside his window climbing a tree for fruit; a co-worker who tells him that films made in North Korea are “boring.” But that’s about it.

Drenched in somber gray tones, Delisle’s graphic novelization of the country does seem to capture the feel of the place. And while the medium may lack some of the emotional impact of a good narrative, “Pyongyang” is funny and insightful and even at times touching.

But most important, it’s probably the closest any of us will get to the walled off country until the abandoned hotels crumble, the regime falls and this mausoleum to the delusions of the past finally opens its doors and lets the world in.![]()