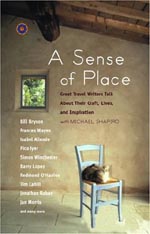

Michael Shapiro: A Sense of Place

Travel Interviews: Jim Benning asks the travel writer about his new book and his encounters with the world's best travel writers

09.01.04 | 8:10 PM ET

Travel writers usually wander the globe to capture places. But Michael Shapiro has been on a different kind of quest over the last couple of years: He was wandering the globe to meet great travel writers, and not while they were on the road, but while they were at home, with their bags unpacked. “I was curious,” he writes, “about what influenced their choices of places and whether being rooted somewhere helped them understand the world.” He visited Simon Winchester in Massachusetts, Pico Iyer in Santa Barbara and Jan Morris in Wales. He met Rick Steves in Seattle and Frances Mayes in Tuscany. He crashed on Tim Cahill’s couch in Montana. In all, he talked with 18 writers, asking them about their writing, their politics, their travels. The result is A Sense of Place: Great Travel Writers Talk About Their Craft, Lives and Inspiration, published this month. In the introduction, Shapiro writes about the project, as well as the death of his father, which occurred while he was working on the book. “A Sense of Place” is packed with thoughtful, wide-ranging interviews. But more than that, the book has heart. It reflects Shapiro’s passion for travel and literature. It’s a must-read for anyone who loves travel and travel writing. Shapiro and I traded e-mails recently.

World Hum: What inspired you to do this book? Since college I’ve been inspired by the world’s best travel writers, by their adventures, their perspectives and their thoughtfulness. Since 1999, I’ve been teaching at an annual travel writers seminar near San Francisco, and I’ve had the great pleasure of teaching with legends including Jan Morris, Peter Matthiessen, Pico Iyer and Tim Cahill. I realized there was so much wisdom and insight flashing around that workshop and hoped to go deeper and share some of this knowledge with the larger community of travelers and writers. I was amazed and gratified that every writer I approached eventually agreed to be interviewed for “A Sense of Place.”

You wrote in the introduction that you viewed doing the travel and interviews as a form of graduate school. I loved that because I’ve always justified the cost of travel as just that—an education. If this was a form of graduate school, what did you learn?

It was the best graduate school I could imagine and I learned from each author I met. I feel that some of the lessons will continue to unfold over the years. It’s difficult to sum up so much briefly, but I’ll cite a few things. From Simon Winchester I learned about discipline and process; he’s in his office by 6:10 a.m. daily and sticks to a rigorous routine.

From Pico Iyer I learned the importance of openness and preparation: His writing sparkles because he travels with Beginner’s Mind, but he also prepares himself well. He’s a voracious reader so he recognizes what he’s seeing.

From Frances Mayes I learned the value of following one’s gut feeling or instinct. She saw that house in Tuscany and even though she couldn’t really afford it she forged ahead and bought it. She knew it would change her life and took a huge risk, one that paid off in ways she never imagined.

From Arthur Frommer I learned about gumption and self-confidence: He couldn’t wait to see Europe when he was stationed there as a soldier in 1953 and couldn’t wait to share his discoveries in a short guide for his fellow GIs. Then, while he was working as a lawyer with a prestigious firm in New York, he self-published “Europe on 5 Dollars a Day,” which became a huge hit.

From Jan Morris and several others, I learned the value of one’s home and place. Morris is deeply Welsh and gains strength and solace from her 18th-century Welsh slate home. Peter Matthiessen has lived in the same home on eastern Long Island since 1960 . When I asked him why he said quietly, almost under his breath, “Things in place.” There’s so much more in the book. The whole journey was a spiral of learning.

Were your encounters with these writers everything you hoped for?

Everything I hoped for and more, but I tried to contain my expectations and follow Pico’s lead of traveling with Beginner’s Mind, just being open to whatever comes up. And as a journalist I’ve interviewed lots of very accomplished people (politicians, athletes, artists, etc.) who aren’t always kind or open. I knew several of these writers already, and knew they were kind people, but with others I wasn’t sure what to expect.

So many of these authors went far beyond what I asked and surprised me with their generosity. Frances and Ed Mayes unexpectedly drove down from Cortona (their hill town in Tuscany) to pick me up at the train station. Luckily I recognized Frances from the picture on her book jacket and they took me to lunch before our interview.

Jan Morris spent the day with me and toured me around her corner of Wales. Tim Cahill invited me to crash on his couch and the next day we drove over dusty roads from his home in Livingston to the cabin where he writes, just north of Yellowstone. We spent a few hours pulling his water pipes from a nearby creek and cleaning out his gutters. It felt good to offer something back after he’d been so generous to me.

Often I was a bit nervous when I met some of these writers, for example the professorial Jonathan Raban and the exacting Peter Matthiessen. But a half hour into our interview Raban uncorked a bottle of wine and I relaxed. The interview gets noticeably better then. I really didn’t expect more than an hour or two from any of these writers, but many of them invited me into their lives in ways I couldn’t have expected. Raban and I had dinner together at a nearby restaurant after our interview and Matthiessen gave me a tour of his home and zendo.

Redmond and Belinda O’Hanlon invited me for dinner at Pelican House, their home near Oxford, which felt like stepping back into the 19th century. And now I feel I have a genuine friendship with several of these writers: Cahill has invited me back to Montana and Pico Iyer and I continue our e-mail correspondence, with topics ranging from Van Morrison to the Wright brothers.

Was one writer any more instructive than the others regarding the secrets of successful travel writing?

I did learn from each of them but especially liked what Bill Bryson said: There is no secret, it’s just hard work and preparation. Here’s an excerpt:

“People think there’s some trick to getting published, that all publishers just reject everything that comes to them and that there’s no way you can break in, as if the people who are published are pre-ordained, that they were given the secret. All writers were once aspiring writers . We were all in exactly that same position and it wasn’t some magic trick. All the time I get letters from people asking, what’s the secret, like there’s some incantation. The secret is you just pound a path to the top of the mountain. You don’t just sort of levitate your way up. Writing is hard work, but it’s a myth that earning money and succeeding at writing is hard work. Becoming Stephen King or John Grisham takes a lot of talent and hard work and luck, but just getting stuff published and earning an income—I don’t think is that hard for the simple reason that there are so many outlets now. It’s not easy, but it’s not nearly as impossible as a lot of aspiring writers think. If you apply yourself and become specialized in an area and create a little niche for yourself, it’s not that hard. It might be hard to make a really good living at it but it’s not that hard to generate some kind of an income.”

I think Pico Iyer’s story is instructive too. He was getting his Ph.D. in literature at Harvard but deep down didn’t want to become a professor. So he wrote book reviews for small magazines and when the Time recruiter came to Harvard, Pico had clips to show him. You can’t always count on getting breaks, but if you’re ready to capitalize on good fortune, I think you have a way of making your own luck.

You traveled far and wide. What was the greatest discovery you made or the biggest surprise you found along the way?

I was impressed that each writer’s path has been unique and yet there are so many connections among them. One example from my Afterword:

“As I re-read Bryson’s ‘A Walk in the Woods,’ I came across a line where Bryson writes that Indians would ‘porcupine’ a grizzly bear with arrows. A few years ago my editor at the San Francisco Chronicle, John Flinn, cited this as an example of a colorful verb, and Flinn used it in a story about donating a kidney to his wife, saying physicians were ‘porcupining’ their arms with needles. I vaguely recalled seeing ‘porcupine’ somewhere else, but it wasn’t until I went back to O’Hanlon’s ‘Into the Heart of Borneo’ that I found O’Hanlon fearing his traveling companion James might get ‘porcupined about the rear with poison darts.’ So, to bring it all back home, I used ‘porcupine’ as a verb in the introduction to my conversation with O’Hanlon.”

I was also surprised about how important their homes were to them. As frequent travelers I wasn’t sure home would be so vital for these writers. Here’s an excerpt also from the Afterword:

“As I traveled from place to place, I wondered: How much do these great travelers and writers care about where they live? As frequent travelers, is their home important, or is travel their priority? I found that all the writers profiled in these pages care very much about where they live and that each is shaped in some way by the places, exterior as well as interior, they’ve chosen to call home. Tim Cahill said it best when he cited a weightlifting expression: ‘You can’t shoot a cannon from a canoe.’ I especially appreciate how several writers have named their houses. The O’Hanlons reside in Pelican House; Jan Morris lives in Trefan Morys, and Frances Mayes’s Tuscan home is aptly called Bramasole, yearning for the sun. Such personalization gives these houses a presence and enhances their personality, an acknowledgment that a home is a being in its own right.”

Were you able to draw any conclusions about what makes a great travel writer? Are there any qualities these writers all share?

One quality that came to the fore is an insatiable curiosity about the world and its people. These writers deeply care not only about their neighbors but about people and places on the other side of the planet. They’re also extraordinarily hard workers; many of them work seven days a week when immersed in writing a book, but they don’t seem to be workaholics, just intensely interested in what they’re doing.

Did you have trouble convincing any of these writers to be interviewed?

Most of these writers were willing but it was tough coordinating our schedules, since they travel frequently. One of the toughest to convince was Peter Matthiessen, who initially agreed and said, Call me when you get to New York. When I got there last January he said he didn’t have the heart to do an interview that week, but I returned on my way back from the UK in March and we did the interview as my deadline approached. Paul Theroux was also challenging: After almost a year of requests he consented to an e-mail interview. He was the only one I didn’t meet in person and was a bit prickly at times during our e-mail conversation. But when I pushed back, he seemed to respect me more and gave me good answers. I asked him why he chooses to live on Oahu and spend summers in Cape Cod. He shot back: “Is that a serious question?” When I told him it was he told me he liked spending summers near where he grew up in Massachusetts and that he spends the rest of the year near the sea because “There is something magical about marine sunlight. I also subscribe to the ancient Phoenician belief that a day spent on the sea is a day that is not deducted from your life.”

Who was the toughest interview?

Theroux, because I wasn’t in the same room with him. You get so much by seeing a facial expression or a gesture, just sensing things intuitively or energetically when you’re interviewing someone face to face. But I did meet Theroux a week later in San Francisco and he couldn’t have been nicer.

Simon Winchester, among others, makes the point that he doesn’t want to be known as a travel writer but simply as a writer. He believes that “travel writer” implies his writing is intended to help readers plan their holidays. It’s largely a debate over semantics, but the question arises often. What do you think about the title “travel writer”? Who should it refer to?

I think it’s up to each writer. Winchester, Morris and of course Allende aren’t travel writers; I think Theroux is (when he’s writing about his journeys). Other writers, such as Raban and O’Hanlon, write travel books that read like novels, so perhaps they’re not really travel books. Ultimately, I don’t feel it’s an important distinction.

Which writer’s home impressed you the most?

The three that made the deepest impression on me were those belonging to Jan Morris, Redmond O’Hanlon and Frances Mayes. Morris is so thoroughly of her place; her weathervane even has the Welsh letters for the two of the four directions. And her home, Trefan Morys, is so solid, you know those stone walls erected in the 18th century will stand for many centuries to come.

O’Hanlon’s home, Pelican House, has no trace of modernity; the walls are crammed with musty texts and specimens, like a vial with the tiny South American fish that can swim up one’s penis. And Mayes’s home, Bramasole, is very touching to see in person: the muted pastel fresco she uncovered on the dining room wall, the Polonia wall, the shrine outside laden with flowers and other offerings.

You discussed politics and the state of travel with a number of writers. Did you draw any general conclusions about the way travel has influenced their worldviews?

Well, there’s not a uniform political opinion but I think these writers have great respect for the diversity and complexity of the world. They don’t try to simplify things into polar viewpoints, like American talk show hosts do. Many of these writers, including Matthiessen, Allende, Raban and Theroux are what some would call liberal or progressive, but I don’t think they’re doctrinaire. They record what they see and then turn it over in their minds before writing respectfully about their travels, encounters and discoveries. But I think by seeing so much of the world they see the result of decisions made in the White House, at the World Bank or in corporate boardrooms. They see the suffering that’s so often engendered by these decisions, and I think it opens their hearts in ways that would be almost impossible if they hadn’t traveled extensively.

Thomas Jefferson once remarked that travel makes people wiser but less happy. I’m not sure I agree. I know you’re not a psychologist, but do you believe these writers are less happy for their travels? What was your impression?

I think they’re the type of people who’d be much less happy if they stayed at home. Their curiosity would be stifled and they wouldn’t feel whole. So I’d say that overall they’re far happier and much more fulfilled because they can travel. As an aside, I don’t think travel always makes one wiser; there are millions of people who travel abroad every year who don’t meet any locals except for the taxi drivers, waiters and hotel clerks who serve them. I think travel is only broadening if you seek out genuine connections with locals. This is not to demean those who take a tour. I think you can go on a tour and still learn a great deal and meet locals wherever you go.

You write at the end of the introduction that the book project has enriched your life “in ways that are just starting to become fully apparent.” How so?

In a way I still feel it’s too soon to say. I wrote that introduction four or five months ago. But I do feel these encounters have made me more sensitive about the struggles half the world’s population faces every day. Bill Bryson and I talked about his trip to Africa where so many people he met had barely enough food for the day and so little hope of bettering their situation. O’Hanlon traveled in central Africa and met people who just wanted a book, any book. One young man desperately wanted an education but had no way to leave the Congo and pursue his dream.

On a personal note, I learned I could write, and somehow write well, under the most difficult circumstances. As I discuss in the introduction, after completing only three of the eighteen interviews, my father was diagnosed with inoperable cancer of the pancreas. In the most trying year of my life, I managed to complete the other fifteen interviews, write introductions to the chapters, shoot and edit the photos, and proofread the book three times to meet our deadline of publishing the book this September. Initially I was amazed that I was able to work at this level while coming to terms with my father’s dying; only recently I’m realizing that it’s probably because of all I was going through that I could write as well as I did. In some way my grief and pain blew away all the self-constructed barriers between me and that mysterious source of soul, and cleared the channel through which inspired writing or music or art can flow. I also believe I sought refuge in the work and at times lost myself in it, clinging to the project like a life raft so I wouldn’t be inundated by a torrent of feelings and emotions.

In a way, I’m still clinging to that journey and all its wonderful encounters with people who started out as my literary heroes and who in many cases are now my friends.

Thanks very much.![]()

Bottom photo features the author with Jan Morris, Tim Cahill, Jeff Greenwald and Travelers’ Tales editor Larry Habegger.

The book’s introduction, an excerpt from the Tim Cahill section and more can be found here.