Rock the Favela

Speaker's Corner: In an excerpt from the book "Culture is Our Weapon," Brazilian musician Caetano Veloso explores the power of AfroReggae in Rio

02.23.10 | 10:47 AM ET

Favela da Rocinha and, behind it, Rio de Janeiro. (iStockPhoto)

Favela da Rocinha and, behind it, Rio de Janeiro. (iStockPhoto)I am not from Rio de Janeiro originally but from a small town in Bahia, so I remember how, as a kid, we all used to look to this city for inspiration. It was, of course, the capital during the Empire and then the Republic, but it was also the cultural capital of Brazil. I remember going to the cinema in the 1950s and the images we’d see of the city: Copacabana beach, Sugarloaf, Christ the Redeemer, samba and Carnival. And, of course, the favelas.

It may seem hard to believe now but, traditionally, Rio is a city that has been proud of its favelas and all the cultural expressions that have emerged from them. São Paulo, for example, is different: The poor areas are a long way from the center, so rich and poor don’t feel like they belong to the same town. But in Rio, many favelas are at the heart of the city and they’ve always been a source of pride for the whole population.

In my teens, I remember sambas praising the particular beauty and happiness of favela life and later, in the 1970s, I often used to visit favelas like Mangueira myself. Even now, you’ll find the richest and most chic families joining the samba parades because they’re Cariocas and they love to celebrate the culture. But these days something has changed.

Historically, the basic difficulty facing Brazil has always been the enormous disparity of wealth between rich and poor. All things considered Brazil is a very convivial country but this huge poverty gap is an invitation to violence. Now add drug trafficking to that situation and see what happens.

I’m not an expert but I guess it began in the early 1980s: People in the favelas began to deal cocaine and suddenly some of the poorest people became very rich and powerful. Suddenly they were dealing with large amounts of money and they were able to buy weapons, police, politicians, judges and lawyers. Of course, the irony is that it never secures these people a bourgeois lifestyle. They may be rich and powerful but they can’t leave the favelas for fear of their lives, and they usually die young. This is the reality.

I’m not an expert but I guess it began in the early 1980s: People in the favelas began to deal cocaine and suddenly some of the poorest people became very rich and powerful. Suddenly they were dealing with large amounts of money and they were able to buy weapons, police, politicians, judges and lawyers. Of course, the irony is that it never secures these people a bourgeois lifestyle. They may be rich and powerful but they can’t leave the favelas for fear of their lives, and they usually die young. This is the reality.

In the past, even the criminals in the favela were seen as somehow charming. I recorded a version of the song Charles Anjo 45 and, with the benefit of hindsight, I can see that this song is a landmark, a turning point. By the time we recorded “Charles Anjo 45,” he was already a character that was saluted with gunshots. You see, Jorge Ben (who wrote the song) is from Tijuca and that was precisely the kind of place where this new kind of criminality was beginning to spring up.

It is true that, even now, the gangsters in Rio have some kind of charm, but the levels of violence and fear have changed beyond recognition because of the drug trade. These days, I’m sorry to say, people are afraid and the face of the city has been transformed. Look at the way all the buildings in Zona Sul are guarded by barriers, security devices and armored cars. This situation of fear and violence is the one in which AfroReggae do their work.

I first came across [the band] AfroReggae when they were just kids playing percussion. I can’t remember exactly when it was nor who invited me, but I know it was 1993, because it was just after the police massacred 21 civilians in Vigário Geral and I knew this group had been put together in response to that horror. I saw them perform in a hotel not far from Ipanema and, on that first occasion, I was simply impressed by their innocence. At the time, they were just kids imitating percussion groups from Bahia; that’s what they did at the very beginning, and that’s how I got to know them.

Later, I discovered that it was Junior who’d put them together and that he’d done other work in these poor communities, including the newspaper AfroReggae Noticias. So I kept my eye on them and we began to interact and a little later they asked me to be their official godfather, with the actress Regina Casé as their godmother.

Over the years, I have seen the progress of AfroReggae, and their development has been unbelievable. They have worked incredibly hard and are very serious about what they do, but they also work joyfully. I don’t know much about the work of other NGOs, but I do know about music and they do it incredibly well.

There is still a lot of fabulous music coming from the favelas: samba, of course, but now funk and hip hop, too. AfroReggae are closest to hip hop but they mix it with other things that other groups don’t. It’s not fusion; rather they put different styles side by side and create contrasts. I admire the way they compose their music, creating cuts and edits as in a movie. It’s beautiful and very modern. I believe AfroReggae are unique and I’m proud to be associated with them. To be honest, even if their ideology was wrong and they were not about helping people any more, they’d still be interesting because they’re an important band.

But AfroReggae are about helping people. As I got to know them, so I got to know their community. They took me to Vigário Geral and I learned a lot about the environment in which they work, and the war culture that is nurtured by the drug trade. I have seen for myself very young children handling heavy weapons and it’s still unbelievable to me. But AfroReggae? These guys teach younger children how to play and, in doing so, they keep them out of the trafficking. They have built houses of culture and music right in the middle of all this violence.

There are not many reasons to be optimistic in Rio right now. It is a complex situation in which violence and fear are on the rise and nobody seems to have a solution. But even amidst all these difficulties you can find some examples of beauty and excellence that give us all hope. This is what AfroReggae represent.![]()

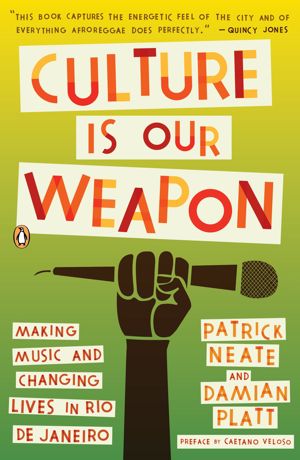

Reprinted by arrangement with Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from Culture is Our Weapon by Patrick Neate and Damian Platt. Copyright (c) 2006 Patrick Neate and Damian Platt.