Interview with Doug Mack: ‘Europe on 5 Wrong Turns a Day’

Travel Interviews: Leif Pettersen talks to the author about his new book, travel snobbery, and traveling with "Europe on Five Dollars a Day"

04.02.12 | 10:50 AM ET

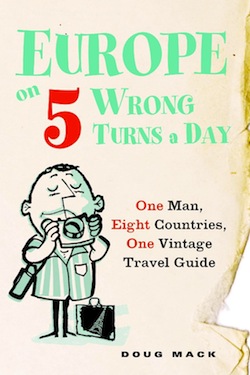

In his first book, Europe on 5 Wrong Turns a Day: One Man, Eight Countries, One Vintage Travel Guide, Doug Mack journeys to Europe with a tattered 1963 edition of “Europe on Five Dollars a Day,” attempting to make his way around the continent relying solely on the advice of the almost 50-year-old travel guide. He forgoes a number of modern conveniences, too. The ensuing hijinks, augmented by his mother’s letters from her European tour in the late 1960s, fuel Mack’s narrative, illustrating how the classic tourist experience has—and hasn’t—changed since Arthur Frommer’s seminal guidebook made European travel accessible to all. With the book coming out this week, Leif Pettersen quizzed Mack, a longtime World Hum contributor, on his contrarian approach to travel and the sweet glow of scoring his first book deal.

In his first book, Europe on 5 Wrong Turns a Day: One Man, Eight Countries, One Vintage Travel Guide, Doug Mack journeys to Europe with a tattered 1963 edition of “Europe on Five Dollars a Day,” attempting to make his way around the continent relying solely on the advice of the almost 50-year-old travel guide. He forgoes a number of modern conveniences, too. The ensuing hijinks, augmented by his mother’s letters from her European tour in the late 1960s, fuel Mack’s narrative, illustrating how the classic tourist experience has—and hasn’t—changed since Arthur Frommer’s seminal guidebook made European travel accessible to all. With the book coming out this week, Leif Pettersen quizzed Mack, a longtime World Hum contributor, on his contrarian approach to travel and the sweet glow of scoring his first book deal.

World Hum: What came first, the “Five Wrong Turns” hook or the resolve to pursue a book deal?

Doug Mack: The hook. I mean, I’ve always liked the idea of writing a book (or, more accurately, to have somehow written a book without actually putting in the effort), but, truthfully, I had never thought about it in tangible terms—it was sort of an idle, unpursued dream rather than a burning ambition. But when I discovered that 1963 copy of “Europe on Five Dollars a Day” and first looked through my mother’s letters from her days as a hippie Grand Tourist, that changed in approximately 2.4 seconds—it was one of those light bulb-over-the-head moments that happens in movies but not in real life. BOOK. MUST WRITE.

In the book, you talk a lot about embracing the well-trod path. Is that something you’d like to see more travelers doing?

I’d like to see people end the snobbery. Last winter, here in Minneapolis, there was a light rail train wrapped in a huge ad for package tours—golf, shopping, the usual—to Mexico. The main slogan, in foot-high letters: “Mazatlan for travelers not tourists.” Does that expression mean anything anymore? On the first page of my 1963 guidebook, Frommer says that it’s a book “for tourists”; he doesn’t use the word with irony or as an insult, he’s just calling them precisely what they are. There should be no shame in that (as Evelyn Waugh quipped in 1934, “The tourist is the other fellow”—someone else, not you).

I’d like to see people end the snobbery. Last winter, here in Minneapolis, there was a light rail train wrapped in a huge ad for package tours—golf, shopping, the usual—to Mexico. The main slogan, in foot-high letters: “Mazatlan for travelers not tourists.” Does that expression mean anything anymore? On the first page of my 1963 guidebook, Frommer says that it’s a book “for tourists”; he doesn’t use the word with irony or as an insult, he’s just calling them precisely what they are. There should be no shame in that (as Evelyn Waugh quipped in 1934, “The tourist is the other fellow”—someone else, not you).

Tourism has always been, to some degree, an act of status, a statement that you have the time, money, and ability to go abroad. With the budget travel boom of the 1960s, though, it exploded and fragmented, open to more people and more ways of showing off, including not just conspicuous consumption but conspicuous frugality. Today, specific travel attitudes and methodologies are as carefully calibrated as attire worn on a first date. Which is absurd. It’s absurd when it means visiting only the most famous cities and landmarks, strictly hewing to the instructions of the latest Frommer’s or Lonely Planet. It’s equally absurd when it means avoiding cities or landmarks for the sole reason that they’re popular. The net effect is the same, an attitude that views travel as a collection of merit badges to be earned, then flaunted: Saw This, Did That, Stayed at the Four Seasons, Slept in a Ditch.

But each attitude completely misses Frommer’s essential underlying point: What matters is not finding something your friends haven’t found but appreciating and understanding that thing—that culture, that place, that food—on your own terms. You can be close-minded even off the beaten path; you can discover all kinds of interesting and wonderful things even on the most tourist-swarmed landmark.

If you were going to do this trip all over again using modern resources, what would you rely on most?

I would at least glance through a modern guideboook and phrasebook so that I could have a better understanding of the basics of how to understand and get by in a given place and culture. I would also use Twitter or other social media to try to make connections with locals before I left (and those people could also have helped me understand more about the culture and the background). Mind you, I enjoyed having to make the extra effort on all of those fronts—understanding the culture, meeting new people. I had to be very attuned to my surroundings, and I enjoyed that sense that my brain was always working on overdrive to figure things out. Being out of your element has its benefits. But there can and should be a balance, and sometimes I found that being ignorant and out of touch led not to lessons learned or serendipitous discoveries but merely to frustration and fatigue. See: my entire time in Venice, where I was eternally lost and where every restaurant I found seemed to have Maestro Boyardee running the kitchen.

Of the places you visited, which one most resembled Frommer’s 1963 description?

Probably Rome. You turn any given corner there and it’s all but given that you’ll suddenly be in front of some ancient and important and impressive landmark—the Forum, the Trevi Fountain, the Spanish Steps. The same places that have been drawing delighted tourists for hundreds of years. There was a deli there, Il Delfino, that was almost exactly as Frommer had described it, and where all the patrons seemed to be older, like they could have been there since 1963. From the built environment to the general culture to the relatively high number of Frommer-recommended hotels and restaurants that were still open today, Rome was more or less what I expected based on Frommer’s (and my mother’s) descriptions.

Which was the most unrecognizable?

It’s a toss-up between Berlin and Madrid, since both of those cities and countries had decidedly complicated political situations back then (Iron Curtain, Franco ...). Obviously, Berlin is twice the city it once was, for tourist purposes. In my guidebook, Frommer notes that you can go to East Berlin as a tourist—the wall was there to keep Easterners in, not visitors out, per se—but that it was bleak and not really worth the trip. If you did go, Frommer recommended that you “register your name with the American MPs at Checkpoint Charlie, tell them the time at which you plan to return, and if you’re not there, they’ll take action.” (Let us pause to give thanks that World War III was not inadvertently started by a tardy tourist.) Today, Checkpoint Charlie is a quintessential tourist trap, where you can pay to get your picture taken with guys dressed as American and East German soldiers and then pop across the street for some Subway at the food court called Snackpoint Charlie. (Once again, I am not making any of this up.)

Also, the former East Berlin is the new tourist center of town, in part because that’s where many of the flashiest bars and restaurants are located, and in part because that’s where you can go to get your Cold War kitsch fix, an important part of the modern tourist itinerary. Take a ride in a clunky Soviet-era car; look at some Eastern Bloc architecture; buy some old Soviet military uniforms from one of the many sidewalk vendors. It’s ... pretty jarring to see the Cold War themed and packaged as a tourist commodity.

Thanks, Doug.![]()

Related: Old Guidebook, New Life, the introduction to “Europe on 5 Wrong Turns a Day”

Sokobanja 04.24.12 | 2:09 AM ET

Hey very nice blog!

Trip to India 04.26.12 | 5:52 AM ET

Hi Doug Mack,

There are many things we can implement to make our journey better and experience world class hospitality. The image with 2 pigeons are captured at the right time. Seems like they also enjoying the click. Nice interview with all details.

Cheers,

http://www.atriptoindia.com/

Melinda 05.14.12 | 2:25 PM ET

The book sounds intriguing. What kinds of things are in the book? Is it a guidebook or more of a narrative?