Pico Iyer: On ‘The Open Road’ and 30 Years With the Dalai Lama

Travel Interviews: The iconic travel writer's new book taps into his personal experiences with the Dalai Lama. Kevin Capp asks him about the exiled spiritual leader's "global journey."

03.25.08 | 1:48 PM ET

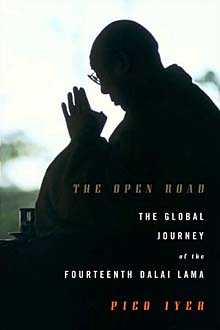

Pico Iyer’s new book The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, which hits bookstores today, is a gorgeously wrought dissection of the Tibetan spiritual leader’s peripatetic life, philosophy and status as an iconic figure throughout the world. While not a work of travel literature in a strict sense, it is infused with vivid descriptions of the many places where the quiet monk takes his message of peace and understanding, particularly his headquarters-in-exile, in Dharamsala, India.

Pico Iyer’s new book The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, which hits bookstores today, is a gorgeously wrought dissection of the Tibetan spiritual leader’s peripatetic life, philosophy and status as an iconic figure throughout the world. While not a work of travel literature in a strict sense, it is infused with vivid descriptions of the many places where the quiet monk takes his message of peace and understanding, particularly his headquarters-in-exile, in Dharamsala, India.

In Iyer’s first interview about the work, I talked with him by phone Monday from Santa Barbara, where he lives three months out of the year.

World Hum: How long did it take you to research and write “The Open Road”?

Pico Iyer: On some level, I would say 30 years, which is how long I’ve been following the Dalai Lama around the world. But intensively—five years. I decided just when the war in Iraq broke out that maybe this would be the time both to put together my, at that point, 25 years of experiences with the Dalai Lama, and most of all, I suppose, to try to see what he might be able to offer to a world that seemed ever more fractured and polarized.

So it began with this first meeting that you had with your father and the Dalai Lama?

That’s right. That’s when I was 17, in 1974, and although, as you read, I wasn’t that excited about meeting [chuckles] a colleague of my father’s, I think that some seed was sown in that initial meeting, which meant that the very first time the Dalai Lama came to the U.S., which was five years later, in 1979, I made sure to go and see him.

Could you trace the outline of his international rise to prominence and how you view it within the global community?

He and anyone who thinks about Tibet would date it very precisely to when he won the Nobel Prize in 1989. I remember in the mid-80s he was coming to New York, and I set up a lunch for the Dalai Lama to meet various prominent editors. One day before the lunch, one of the editors called up and said, “Cancel it. We don’t want to come into the office on a Monday morning just to meet a Tibetan monk.” And, literally, five years later, some of the same people were flying all the way from New York to Dharamsala just for a 15-minute interview with him.

There’s an anecdote in the book in which you describe riding around with a journalist acquaintance who was disappointed with the Dalai Lama, who felt that he was too simplistic, almost childish, maybe not even that intelligent. Do you think that that relates to this almost iconic status the Dalai Lama has achieved? Are people bound to be disappointed when they first meet him because they have so many preconceptions about him?

It’s interesting you say that, because that whole chapter is about projection and exactly about all the expectations and ideas we bring to him. But I think in terms of a backlash—not exactly a backlash—but the sense quickly that he was everywhere, and one saw his face in every bookshop, and one heard so much about him that people who never had listened to him and had never seen him assumed, “Well, this must be hype, and he must be the media man of the moment. It must be just a passing fascination.” And that’s very understandable.

One of the book’s charms is that it feels like a journey along that open road, that central image in the book. I also sensed that, as the book progressed, you became more confident in engaging him and his ideas in a debate.

I’m sure you’re right, and I hadn’t quite thought about it in those terms, but that’s very much the hope. So I’m really happy if that’s the way it came out, because I think books are only as exciting as the sense of discovery that we bring to them, and precisely that notion of a journey in any narrative is what holds the reader’s attention, as you travel, not necessarily from ignorance to knowledge, but ignorance to a deeper ignorance [laughs], or to a sense of how much you don’t know, at least.

I took a lot of trouble choosing the title of “The Open Road,” partly because, in some ways, I do see this as a travel book, and when I think of travel, and any of the travel books I’ve written, the real meaning of them is trying to see the world through different eyes. It’s a journey into a different perspective for me.

So this book was, for me, a travel book in the same sense, because it was a journey into how the world looks to a Tibetan Buddhist, and someone who’s really pursued that pathway deeply.

But the book also feels like a genre-hybrid. Were you consciously setting out to blend genres, or is that just something that arises out of the process, and that kind of labeling is left to the marketing department at Knopf [the publisher]?

[Laughs] Well that’s often the case, but it was a very, very conscious choice here. Clearly, the big challenge for me was that so much was known and so much has been done and brought into the world very powerfully about the Dalai Lama. What new is there to say?

And secondly, even by 2003, when I began it, I’d been writing about Tibet for 10 years—no 20 years—by then, so what more could I say? So, in each chapter, I’m approaching a different side of him. But I’m also coming at him from a different side of myself. So one chapter might read somewhat like memoir, and the next would read like journalistic cross-questioning, and the next would read like two people sitting, meditating in a room, and the next would read like a traveler finding himself in this wild global village called Dharamsala.

When do you know when to assert your own identity within the narrative?

In this book, I wanted to give it a very strong, personal quality, having to do with, as you said, my journey, and my developing an acquaintance with him over 35 years.

But I also—especially because it’s the Dalai Lama—wanted to leave myself as invisible as possible. One of the things that I felt I was beginning to understand about Buddhism and the Dalai Lama as I progressed through the book was that the Dalai Lama himself wasn’t important, except insofar as he challenges or encourages us to be different in ourselves.

What do you hope, if anything, your book will accomplish, especially at this moment, with the protests and renewed attention on Tibet?

The only thing I can hope to achieve is to elucidate and, maybe, illuminate for people exactly what lies at the heart of the Dalai Lama’s thinking and, as it were, where he’s coming from in the positions that he takes.

So, I suppose, my hope would be that somebody who’s watching this and is confused and doesn’t know what to make of it, know what to make of the Dalai Lama’s take on it, might pick up this book and come away knowing a little bit more.![]()

Editors’ note: The Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

MargoWolf 03.28.08 | 9:58 PM ET

It was a surprise when a search to add information to an activist blog I writeat MySpace came up with your brand new book. My readership is growing and they need to have shared interests so I hope they will read this book. I want to, as soon as I am able. Thank-you for sharing an account about His Holiness, unexpectedly, at a most opportune time for him and the brave people of Tibet. There are few personalities that have been such a draw as this man’s. He represents the best in a foundering world. Maybe he will have his wish to go home to his people. I am skeptical; even if the Chinese back off the Tibetans, in my opinion, they won’t let him return. To allow that would mean to lose face, as they have already. What I find hard to believe is that the Chinese people themselves would ever disrespect this man; religion did not die out dispite Moa’s telling the Dalai Lama, long ago,

“Religion is s..t.” Recently His Holiness said “It is not just Tibetans who want freedom, Chinese want it, too.”

Do you think that somehow Tibetan freedom may come if the Chinese themselves achieve a broader freedom, also? I feel that Tibet may be closed again for years, although so many world leaders support the Dalai Lama’s call to an end to violence and a solution to

what we now know has been a genocide by

the Chinese Regime upon the Tibetan people for decades. Your works are always of interest and illuminating.MKW

MargoWolf 03.28.08 | 10:49 PM ET

Sorry, Mao, Not Mao.

MargoWolf 03.30.08 | 12:46 AM ET

Pico Iyer, Today I read your Time Magazine article and, although it addresses my questions and I have heard the Dalai Lama speak of theses things; Tibet and China are as one because the Chinese are there and Tibetans need to learn Chinese. But he has said, if he is wrong about something , convince him. What he sees ahead is what I see ahead, also. I just do not see how the present does any good and the time to stop the violence is come. The Chinese are so rigid. If that were not the case, more may be done for Tibetans now. But who is convincing them that the Tibetans in their present guise of under dog, can be brought forth and given autonomy when they are so downtrodden and lost in their own Kingdom? We all must keep at the Chinese while there is this opportunity that does embarrass them. Can the world create progress inside this attitude the Communist Regime stands behind so powerfully? For a moment I did think they needed help from the outside world but it is so easy for them to deny it and keep Tibet held in their jaws. I want to think I can ask you what will happen, but you don’t know. I can ask what are the other possibilities? And can the violence be stopped ASAP? Some of this is on the heads of those who began this Rebellion, no doubt. But they have something to gain in cooperation if that is even a

term that is raised by the Chinese. Please tell me what you think, I would respect your opinion so.Marilyn Wargo

MargoWolf 04.03.08 | 3:38 PM ET

Pico Iyer, I am sad to see no one else taking up these subjects with you. Your insights are wanted. This interview is

excellent and I know that the book will be gratefully received. Blessings. Marilyn Wargo Travel safe…

fusionpower 04.11.08 | 10:28 PM ET

Pico Iyer is a person without morals. He claims in a New York Times Article he wrote in 1991 that China killed 1.2 million Tibetans. This is a false, and murderous lie! In fact, it was Great Britain, which occupied Tibet at the same time that it Occupied India, that killed those Tibetans. This was the same time that Great Britain killed more than 100 million Indians and 100 million Chinese.

So, another biased view, without factual basis. I am so saddened by the lack of history that western educated people have, particularly from the US and England, two of the worst nations in terms of murder of innocents, in the world. By the way, I am an American Citizen (by birth).

In terms of the Dalai Lama, in 1954 he was a man of peace still. He talked with Mao and they worked together on a deal for an autonomous Tibet, but without the feudal past. Then in 1959, with CIA backing, the Dalai Lama fought a war of violence against China.

Later, the Dalai Lama helped the Diem Regime in US Backed “South Vietnam” kill more than 100,000 Buddhists. Since then, the Dalai Lama has been known throughout China and Vietnam as the butcher of Buddhists.

The Dalai Lama later on went on to support Augusto Pinochet, another butcher.

How did this young man move from peace to war? How sad…

MargoWolf 04.11.08 | 11:15 PM ET

fusionpower, Pico Iyer, I believe you now should come here and say something. It is not my opinion that you are wrong, fusionpower, but that you have read some unusual history. What are your sources? We all know that there are those who believe that Hitler did not kill 6,000,000 Jews and over 1,000,000 Gypsy/Romany peoples. Britain was gone from India and I was a curious ten year old when the Dalai Lama fled Tibet. He had no army and his people were slaughtered. 37,000 or more were killed in Llasa just because he had fled. He had no alies with modern weapons to strike at China. You say that the Dalai Lama was involved in the deaths of Buddhists in Vietnam. If this were remotely true I would know about it. As for Pinochet, I will look into your accusations. I want to say what I do as

accurately as possible. It does not surprise me at this time that someone, such as yourself, would come forward and

say such things. Maybe you have been planted by the hardline Communist Chinese at Pico Iyer’s feet. Could that be? Please say more. Your view is very

revealing.