A Writer’s Port of Call

Travel Stories: Adam Karlin went to Indonesia to work as a reporter. But after a visit to Jakarta's old wharf to see the aging Makassar schooners, he left with a calling of a different order.

04.23.08 | 12:07 PM ET

Call him Ishmael.

He was handsome in the Javanese way: slight and slender, his walnut-brown skin, soot-darkened in the Jakarta night, breaking into a flash of white as he smiled at me.

“Are you a tourist?”

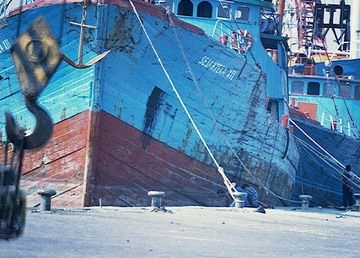

He was the first Indonesian sailor to address me as such on the docks of Sunda Kelapa, the old port of Jakarta, where I had gone at night to see the creaking sails of old Makassar schooners. The combination of being half-Asian, cloaked by darkness, and filthy from two weeks of Indonesian travel meant I was rarely mistaken for a Westerner at night.

I looked at the Javanese who had called out to me. He was surrounded by other sailors, dark-skinned and short-shadowed at night, illuminated in flecks of blood-orange by the cherries of their clove cigarettes. Their eyes flashed with the casual wariness of wharfmen. It seemed silly to approach a group like that at night on the docks, so I did.

“Dari mana? Where are you from?” the first one asked, ticking off the first question most Indonesians ask foreigners.

“Orang America,” I said.

“Speak Bahasa Indonesia?” he asked, the others listening, closer. Even in the dark, I could see their checked sarongs were stained with sweat and betel juice.

“Sedikit.” A little.

“Look like Asian face.” He lifted a slender hand briefly, as if to touch my look-like-Asian face, and then dropped it.

“Bu saya orang Myanmar. Pak saya orang America.” My mother is from Myanmar and father is American. This sparked an intake of understanding breath from the group. Myanmar, Myanmar, they whispered.

“Nama saya Ishmael,” said the first. My name is Ishmael.

Of course it was. The sailor I met in the gothic, faded beauty of the Jakarta docks had to share names with the protagonist of the great gothic American novel, “Moby Dick.” It made sense; the immense, tarnished space and ocean-horizoned adventure that defines Herman Melville’s novel permeates Sunda Kelapa, a sort of towering forest of driftwood and port cranes. In between the berths of Bugis clippers, Indonesian sailors and longshoremen squatted at low tables, puffing on sharp, sweet-smelling kretek cloves, playing cards and devouring bowls of rice and sambal.

Bags of rice were off-loaded onto open-backed trucks, stacked into warm piles by dockworkers who swung their gaff hooks into each sack like a soft body, manipulating the heavy load into neat container molds under the moonlight. Cats scurried from ship to ship, stopping to murder mice and devour fish bones scattered under the kaki lima, “five-legs,” the name of the three-legged pushcarts operated by street peddlers.

Ishmael cocked his head to one side, like a curious crow that had regarded me days before in Jogjakarta’s Pasar Ngasem, the bird market, a sweating bazaar of not just birds, but reptiles, bats and God knows what else. Ishmael stared at me with the same curious, black eyes through the smoke of his kretek.

“How long you stay Indonesia?”

It was a good question. Ostensibly, I was leaving the next day, but part of me had wanted to move here, to stay and make a career of reporting these islands’ news to the wide world. Two weeks earlier, my flight had landed in Bali, and I wandered that brilliant fist of green rice paddy and blue sky like a soldier bereft of a mission. I had originally come to Indonesia on the strength of a tentative stringing assignment with an American newspaper. That position had vanished a few days before I shipped out, and a lot of the work I had done up to that point—moving to Australia to be closer to my girlfriend but closer to Indonesia, as well, taking Indonesian classes, studying the country in graduate school—seemed suddenly pointless.

Ishmael stared. “Sorry?”

“Besok,” I said, coming back to reality. “Tomorrow. I leave tomorrow.”

He nodded. “Want to see my boat?”

It was connected to the docks by two thin planks. Sailors, their wives and their children scampered up and down the walkway. Underneath was the sickly dark water of Jakarta. Earlier that day I had watched a man grill fish on the side of the road, the skin flaking against the blue wood smoke, and thought, I love this sort of street food in the Third World, and then a plastic bag floated by in a river of raw sewage and I remembered, But I hate the water. That poisonous water swirled next to me now, ready to catch me if I fell.

But how many times do you get to board a Makassar schooner? Ishmael led me slowly, gently, grasping my wrist as we inched up the plank over the water. Rainbow slicks of diesel scarred the dark-green surface. It was like the fuel that leaked from a Madura-Surabaya ferry, where naked street children, like brown turtles, slipped into the water, scattered with trash, plant life and huge clouds of multicolored oil. A boy picked up a wet newspaper drifting in the wake of our ferry and began reading it, polluted water dripping from his mouth.

The memory of the kids splashing in the dirty water made me dizzy for a second. Ishmael smiled, his white teeth once again the only light against the harbor’s liquid darkness.

“You OK?”

“Yeah.” My voice didn’t sound as shaky as it felt.

We hopped onto the boat, which had the pleasant, rough lines of a vessel in constant use, like the ones in Maryland, where I grew up. There was no sleek fiberglass, no polished instruments in sight. The gunwales were painted the institutional green of an elementary school wall, the paint cracking under the constant assault of salt breeze.

Ishmael brought me to the cargo deck, now smooth and empty. “Where do you sail?” I asked.

“Kalimantan. We take wood, 400 tons, from Borneo to here, and then cement, the same amount, back to there.”

“Where are the sailors from?”

Everywhere, he said. The sailors spoke different languages but communicated to each other in Bahasa Indonesia; they prayed to different gods but worked together to survive on the archipelago waters, like Indonesia condensed into a boat.

We walked through the berths, candlelit or half lit by swinging, bare light bulbs. Some of the sailors smiled Javanese smiles that took in their eyes, and some of them stared with the suspicious anger I associated with the Madurese.

“Orang Madura?” or Madurese people? I asked Ishmael. He laughed. “Ya. Banyak kusar.” Rough. Very kusar.

I nodded, remembering how I came to Madura to watch the bull races and found them after half a day of searching. I had originally asked on a Madura-bound bus where the races might be found in extremely broken Indonesian, saying something along the lines of, “Where do the cows here go to run fast?” Eventually I was deposited in a small town where English was nonexistent. The races had been worth it—bulls, rubbed down with coconut milk, fed palm liquor and prodded with spiked rings inserted into their anuses, charging through the racetrack and often enough, the crowds, too. But the Madurese had been, in their way, just as foreign. They were not welcoming in the usual Indonesian way. If I made a mistake speaking Indonesian, they wouldn’t smile and correct me, like the Javanese. They would laugh. One farmer told me, with a hint of sardonic pride “Madurese people are kusar”.

Ishmael and I stood on the deck. His English and my Indonesian were both exhausted. We determined our cultures shared an important similarity: in America and Indonesia, boats are named after women.

“Mengapa?” I asked. Why?

Ishmael laughed. “Don’t know.”

Outlined all the way to the edge of Jakarta were, as Joyce puts it in “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,” “the black arms of tall ships that stand against the moon, their tale of distant nations.” An engine coughed to glugging life in the distance, and it occurred to me that I had been wandering these islands like a journalist even if I wasn’t here as one—asking questions, being a reporter, but in a different way from what I had originally imagined. In between the yellow moon glinting off the ships and the choking gurgle of their engines, Ishmael and I made our way back to the docks.

Two weeks in Indonesia might have brought me away from one job, but nudged me closer to another. Back in Australia, I attended a conference for a travel guidebook publisher and my career seemed to be taking off. On the last day of the conference, a business card from the company arrived in the mail. Printed below my name was a tag that said: The wide world is always there, kid.

“Travel Writer.” ![]()

Photo by

Photo by

Terry Ward 04.23.08 | 2:13 PM ET

I loved this story, Adam. I really want to learn Bahasa for next time I go back to Indonesia. Using the language in your writing, as you’ve done with this story, made it really powerful. Felt like I was there on the docks, too. Thanks!

Julia Ross 04.23.08 | 2:49 PM ET

Nice piece, Adam.

John M. Edwards 04.23.08 | 3:59 PM ET

Hi Adam:

I haven’t had time to fully read this story yet, but from a quick scan I can tell it’s a winner. Right now I have the reading-comprehension skills of a grade-schooler taking the Iowa tests.

But I’ve been there, too. The people who live behind the docks, in real shantytowns of corrigated iron and cloth seemed amazed to be seeing a real Dutchman (even though I’m an American Mayflower descendant)—and were friendly without being menacing or annoying. I’d say for very poor people they lived with quiet dignity, and you have to love that portable TV hooked up with a makeshift generator.

I’ve been to Indonesia many times. The Indian poet Rabindranth Tagore said this: “I see India everywhere, but I don’t recognize any of it.” However, in the wharf area, among the aging ships, I said to myself, “Hey, I’ve been to Holland before.” The Dutch East India Company set up some of the most romantic foreign ports of call I can think of.

And I met a lot of Westerners (actually Indonesians with a lot of Dutch heritage) who were quite helpful, including an amusing Indonesian man who resembled Richard Dreyfuss, who kept mentioning that he used to work for The Philips Company while we waited for an ancient ship to try to get us somewhere.

Tim Patterson 04.23.08 | 5:13 PM ET

Gorgeous story, really sensual and smooth, beautifully written. Thanks Adam.

Arun 04.24.08 | 1:37 AM ET

Loved the simplicity elicited through the article. And the way it ended brilliantly. Wishing for more great “Travel Writing”..

Claudine 04.27.08 | 7:09 PM ET

This was an excellent descriptive story. The dialgue drove the story.

Jarrett 04.28.08 | 2:57 AM ET

Excellent writing. We find our callings only by noticing what we’re already doing.

IKEA 04.28.08 | 6:37 AM ET

What is this the story - I cann’t understand it at all!

Kelsey Timmerman 04.29.08 | 11:04 AM ET

Enjoyed it. I especially liked the part balancing above the water on the planks where Adam recollects the swimming children.

We often become what we are without ever realizing it.

Kay Fulgham 04.29.08 | 4:56 PM ET

Your story brought back memories of one of my favorite countries. Unfortunately I didn’t have the nerve to climb the planks.

Thank you.

Tim 05.03.08 | 12:51 PM ET

I was in Jakarta down at the docks about 20 years ago. We hung out with some dock workers,they let us try and carry some bags of cement across those small planks.My buddy and I were both twice as big and strong than most of these guys,but we had a helluva time gettin’those bags across the planks.They did it with ease,it was kinda embarrasing,especially when they gave us a hard time.

Greg 05.07.08 | 4:31 AM ET

Very familiar story! I was in Jakarta!

Eliza 05.16.08 | 10:27 AM ET

wonderful piece! I devoured every bit of it. The Joyce quote was cool, though also surprising, since his use of it on a figurative level alludes to the Irish Catholic church as having lost its domination over Ireland. The masts can be seen as old crosses - monuments of religious nations no longer…