The Mad Matatus of Kenya

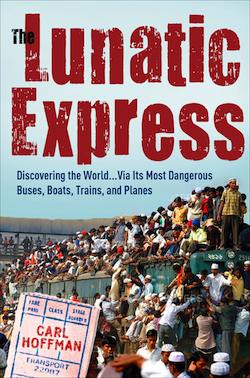

Travel Stories: In an excerpt from "The Lunatic Express," Carl Hoffman spends a sweaty, noisy, desperate 24 hours in Nairobi

03.16.10 | 10:42 AM ET

Matatu mechanics in Nairobi (Photo by Carl Hoffman)

Matatu mechanics in Nairobi (Photo by Carl Hoffman)In the history of dangerous conveyances, Kenya’s matatus stand out. Daniel Arap Moi, the country’s former president, once called them “agents of death and destruction.” In 2004 they caused 3,000 deaths and 11,989 accidents. I wanted to ride them and by luck I found David Wambugo, lounging in his taxi in downtown Nairobi, his feet up on the open doorway. There were thousands of taxis and they were all hustling me, but something about Wambugo caught my eye. He had shoulder-length dreadlocks and the whites of his eyes were as red as if they’d been caught by a too-close camera flash, but there was kindness in them. I hired him to take me to the house where Karen Blixen, the author of “Out of Africa,” had lived, and on the way back into town I asked him if he knew any matatu drivers that I could spend the day with. Yes, he said, and in minutes he was on his cell phone and it was all arranged: He’d pick me up at my hotel at 5 the following morning.

It was still dark the next morning when I left my hotel, and there he was. “Come on,” he said, “they have picked up the matatu and they are on their way.” The streets were still empty, the air cool but smelling of smoke; we were meeting the matatu at its staging point at the Nairobi train station. But even blocks away, we suddenly hit standstill traffic. “There is a problem at the stage,” he said. “Too many matatus.” He swerved onto a side street, cut through traffic, taking a winding, indirect back way. “I have been awake all night, but I am very sharp!” he said, skidding around a tight corner. “We drivers eat mira”—the mildly narcotic drug known elsewhere as qat chewed throughout the Horn of Africa and the Middle East—“and this makes us alert on the road. It is not like beer. Beer you cannot take, but mira you can take and drive. You have to eat first because this juice will not let you eat until the next day. Me, I have not slept or eaten in 36 hours.” Wambugo didn’t own the taxi; he only had access to it two or three days a week, so he chewed qat and drove without sleeping as long as he had it.

Suddenly there we were—at a semicircle packed with matatus, like a thousand ants trying to squeeze into the same hole, all honking and belching exhaust into the darkness. They were all on the very same route, the 111, operating between Ngong Town and the central Nairobi train terminal. “You see, the competition has already started,” Wambugo said, opening a folded piece of paper and extracting two green twigs of qat to chew, while smoking a cigarette.

Wambugo spotted a green Mitsubishi bus slightly bigger than a minivan. “OK, there’s my friend, let’s go,” he said, introducing me to driver Joseph Kimani and tout Wakaba Phillip. It was just getting light; hundreds of matatus, from 14-passenger minivans to 51-passenger buses, were angling, squeezing, honking, pushing, to navigate a semicircle that they entered empty and left full. Kimani, 32, with a wispy mustache and a wiry body, worked the wheel and gears, while Phillip, thirty, ran back and forth waving his arms, shouting and banging on other matatus, trying to leverage Kimani through the madness while enticing passengers. (That’s not all Phillip did, but the other stuff I didn’t see, never saw—it was all too quick, too fluid, too under-the-radar—and didn’t even learn about until midnight, 17 hours later.) Competition was fierce. Every matatu, after all, was angling for the same passengers.

Wambugo spotted a green Mitsubishi bus slightly bigger than a minivan. “OK, there’s my friend, let’s go,” he said, introducing me to driver Joseph Kimani and tout Wakaba Phillip. It was just getting light; hundreds of matatus, from 14-passenger minivans to 51-passenger buses, were angling, squeezing, honking, pushing, to navigate a semicircle that they entered empty and left full. Kimani, 32, with a wispy mustache and a wiry body, worked the wheel and gears, while Phillip, thirty, ran back and forth waving his arms, shouting and banging on other matatus, trying to leverage Kimani through the madness while enticing passengers. (That’s not all Phillip did, but the other stuff I didn’t see, never saw—it was all too quick, too fluid, too under-the-radar—and didn’t even learn about until midnight, 17 hours later.) Competition was fierce. Every matatu, after all, was angling for the same passengers.

The semicircle was 150 yards, tops; passing through it took nearly 45 minutes—think the tank scene in the film “Patton.” Matatus with names like King of the Streetz and Homeboyz were jumping the curb onto the sidewalk, parrying, jockeying, blocking one another’s doors; when we broke free Phillip swung up into the doorway and we blasted up Ngong Road, an undivided two-lane strip of cracked blacktop, with the Bee Gees—there was no escape from them, I was learning, anywhere in the world—at deafening volume.

As he worked the gears and lurched along, Kimani told me he’d been driving matatus for seven years, after a brief career driving trucks. Phillip was moving up; he’d been selling vegetables on the street until two years ago. “Business was bad,” he shouted over the music. “I was very poor.” Both had climbed out of bed around 4 this morning, and picked up the matatu in Ngong Town, in the shadow of the Ngong hills, not far from where I had gone the day before to see Karen Blixen’s coffee farm. Or what’s left of it. “I had a farm in Africa…” is one of those famous literary opening lines, but her elegiac words recall a different, colonial Africa. When we hit Ngong Town an hour and a half later, it was a miasma of overcrowded mud and trash and corrugated shacks, with the occasional rail-thin, six-and-a-half-foot-tall Masai warrior looking like a Hollywood extra still in costume waiting at a bus stop. One man’s pierced earlobe was so long it was wrapped up and double-tied through its hole. The staging area was a football-field-sized patch of mud and banana peels and corn husks and cigarette wrappers and crushed plastic water bottles surrounded by four-foot-square market stalls.

We pulled in, Kimani and Phillip shouted, “Come, Mr. Carl, it’s tea time!” and leaped off the bus. We crossed the mud, crossed the muddy road, waded through garbage, wolfed down fried dough and a somosa and sweet, milky tea in a concrete room, and hit the staging area again. That’s when the complexity of it all started to hit me, the minute economic scale spread over as wide a net as possible. A small army of touts fanned out to fill the bus. “Forty, forty, forty,” they called. “Fortytown, fortytown, fortytown,”—40 shillings to Town. The touts were freelance; Phillip would pay them each 40 or 50 shillings for their work. And ours wasn’t the only matatu; there were dozens here, all doing the same, hiring the same freelance touts, a series of ever smaller layers, both cutting into the profit and spreading it out over as many people as possible.

Back and forth from Town to Ngong we went all day as the traffic built; in places it took 15 minutes to move two blocks—wall-to-wall, bumper-to-bumper matatus honking and flashing their lights and blasting music, some with monitors pumping out music videos. Each matatu spat a continuous, visible plume of gray exhaust, and the fumes were intense, overwhelming. Kimani kept the music at earsplitting volume, from Marvin Gaye to African melodies to Britney Spears, just as the volume had been cranked on the films on all the buses in South America. In America people flipped out if you talked too loudly on your cell phone; in the rest of the world there was so much noise, the very idea of silence was unheard of.

The road had no lane markings and barely a shoulder; for mile after mile it ran past makeshift market stalls and men hauling heavy, two-wheeled carts. Kimani rarely actually stopped the bus—Phillip was like an acrobat climbing over passengers to collect fares, hanging out the doorway to spot them and hurry them on and off the vehicle, banging on the side and whistling loudly to signal Kimani.

On it went, at a grueling pace, the economy of it all hard to grasp. A 14-passenger matatu cost 70 shillings to ride; in a 15-hour day it could make six to seven round trips, taking in 6,000 to 7,000 shillings, about $100. Riding a 51-passenger matatu cost 40 shillings for a vehicle that moved more slowly; it only managed five to six round trips in a day. For passengers the bigger one was slower and thus cheaper; but for the driver and tout, the bigger matatu was better, the volume adding up to more income. Still, a driver and tout like Kimani and Phillip made about KSh 600 a day—10 dollars—paid in cash at the end of every evening. Maybe. “It’s a good job,” Kimani said, his eyes darting from the mirrors, his feet and hands always in motion, “but to succeed, not everyone can do it. You must get up very early and work very long hours.”

The speed, the weaving and honking and cajoling; at first I saw it as some form of romantic African expression. But that was wrong. It was simple economics: Poor people—desperate and hungry—trying to squeeze one more passenger, one more round trip into a day that never seemed to end, a day where literally every shilling counted. On the matatu in Mombasa I’d seen it as a cool, mysterious, and exotic dance—look at those wild Kenyans and their nutty matatus! But now I saw it as it was: A mad scratching for pennies.

At noon we snapped a main front leaf spring, and Kimani sped off to the garage. But it was no garage; it was a place that boggled my mind, that stretched my imagination. It was Dickensian: block after block of mud passageways littered with garbage and upended vehicles and men sleeping on piles of tires and the sparks of welders and the smell of smoke and oil and diesel and Bondo. It was one lane wide, with two-way traffic. It was hot and glaring, a place of burning fires and braziers and hammering and music, and the mud was so dark, so black, so viscous, it was like oil. It was the worst and the most compelling place I had ever seen.

Richard Trillo 03.16.10 | 1:16 PM ET

The best description of the Nairobi matatu scene I’ve ever read. I’m exhausted. Thank you!

Ruth@Exodus 03.19.10 | 1:57 PM ET

Sounds totally crazy! Agree with Richard, exhausted reading it. Sound like you need a holiday!

Brenda 03.20.10 | 4:15 AM ET

Wow,I was sort of skeptical at first but I really enjoyed reading this piece….I live in Nairobi-Kenya and I couldnt agree with you more!!!!!I adore the loud matatus on route 48…Its like being in a mobile nightclub…minus the booze!!!!

Irene 03.20.10 | 4:36 AM ET

I just love Matatus and the buddies who drive them. They give live to the city…....i usually have fun with them while on the road. I go on reading the writings on the sides and some of them they just make my day…........where the law is very strong, there is boredom.

HELLEN 03.25.10 | 3:44 AM ET

Love the exposition and totally agree. I live in Nairobi and I know it can get some getting used to.

Maina 03.25.10 | 4:11 AM ET

i must say, for a man who has lived all his teenage life in Niarobi, among all these robbers, car owners, police-cum-thugs and greasy fingers, i find this article very balanced. you never told us, though, what shocked you the most: the daily struggles, the seemingly insurmountable obstacles or how these “middle” men (Kimani and Phillip) manage to sleep, laugh, etc despite the sea of grease, noise, dirt , violence and hopelessness that you deeply described.

carl hoffman 03.29.10 | 5:35 PM ET

Thanks for all of your comments. Maina, I’m not really shocked by dirt or noise or things like that, but it does always amaze me how people like David and Wakaba could be so cheerful despite such long working hours and noise and traffic and crowds; I guess I always see not hopelessness at all, but a lot of hope. It’s easy to romanticize matatus from here in the USA, and to forget the corruption and danger inherent in them, yet I also wish we had something more like them in Washington, DC - they do lend life and energy and, most of all, efficiency - they’re always there when you need one!

Laurie 04.01.10 | 9:53 AM ET

Great description! I was only in Nairobi about a week but I really enjoyed reading about your experience there. Well said, “exhausting”.

Mwende 04.13.10 | 2:36 AM ET

It’s a great article. One feels amongst the matatu passengers while reading.

Imagine I’ve been so stupid to try and invest in having a matatu.

Guys like David and wakaba have the breakdown fixed for 300 Ksh and they’ll tell the owner in the evening it had costed them 3000 Ksh.

As an owner, i have made not 1 Ksh profit. I pay the driver, i pay the tout, i pay the maintenance and there’s nothing left for me.

I comfort myself in knowing that at least I pay 5 people a day an income ( driver,tout, mechanic, and 2 police guys)