Rolf Potts: Revelations From a Postmodern Travel Writer

Travel Interviews: Rolf Potts discusses how travel writing has changed in the last decade -- and what he sees for the future.

09.19.08 | 8:51 PM ET

Rolf Potts’ body of work is filled with thoughtful, provocative and often-inventive travel writing. It’s clear we like his approach: World Hum has published many of his stories, and he writes the site’s Ask Rolf column. In working with Rolf, it’s also become clear that he’s a student of the history of travel writing, and he’s an evangelist for the deep-diving kind of travel we love.

Rolf Potts’ body of work is filled with thoughtful, provocative and often-inventive travel writing. It’s clear we like his approach: World Hum has published many of his stories, and he writes the site’s Ask Rolf column. In working with Rolf, it’s also become clear that he’s a student of the history of travel writing, and he’s an evangelist for the deep-diving kind of travel we love.

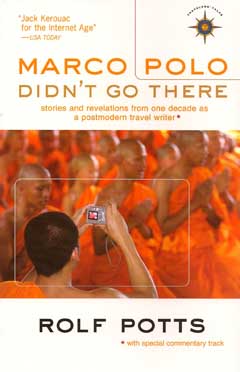

So, to mark the publication of Marco Polo Didn’t Go There: Stories and Revelations From One Decade as a Postmodern Travel Writer, we asked Potts to step back and reflect on travel and travel writing, as well as some intriguing issues facing today’s travelers. Potts took some time out from his virtual book tour to answer questions via email.

World Hum: The collection looks back at a decade in your life as a travel writer. What are some of the major changes you’ve noticed in the genre in the last 10 years?

Rolf Potts: If you’re talking about literary narrative travel writing, it really hasn’t changed all that radically. A good story is still a good story, and a compelling nonfiction travel tale will not just evoke a strong sense of place, it will contain the same human themes and narrative elements as a good work of short fiction. This is as true now as it was 10 or even 50 years ago.

Of course, the motifs and assumptions of well-told travel stories do change over the years. Twenty years ago, for example, books like Pico Iyer’s Video Night in Kathmandu showed how travel writers had a new duty to deal with the charms and challenges and complexities of globalization. By the time I started writing for a living in the late 1990s, it had come to the point where it was nearly impossible to write a travel story without acknowledging globalization in some way. It’s difficult, after all, to project the old exotic clichés onto foreign lands when you keep meeting Burmese Shan refugees who can quote West Coast hip-hop, or Spanish Catholic girls who have crushes on Chinese movie stars, or Jordanian teenagers who idolize Bill Gates.

It’s interesting to see how the recent death of David Foster Wallace has renewed interest in his 1996 essay about cruise ships, A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, which is a shining example of where you can go with travel writing these days. It could be the sentimentalist in me talking, since Wallace’s death is so recent and shocking, but you can actually see his influence in the more imaginative and effective travel writing that has been published in recent years. One of the most memorable travel stories I’ve ever seen in the pages of a men’s magazine was George Saunders’s 2005 GQ essay The New Mecca, which basically examined Dubai in the same madcap spirit that Wallace deconstructed cruise ships. Elsewhere, the first 30 pages of Tom Bissell’s 2003 book Chasing the Sea take us through Uzbek customs in a way that recalls Wallace’s use of painfully specific details to evoke truths as telling as the story arc itself.

It would be an exaggeration to say that Wallace-style experimental narrative has defined the last decade of travel writing—the genre still is and probably always will be dominated by traditional storytelling and reportage. But I think non-traditional narrative has become a way for writers to wriggle into the complexities of postmodern travel and show the reader things they might otherwise have missed. Of all the stories I’ve written over the years, I’ve gotten the most spirited reader response from two of my more experimental travel tales—Storming ‘The Beach’, which was a gonzo-philosophical look at a Leonardo DiCaprio movie that was being filmed in Thailand, and The Art of Writing a Story About Walking Across Andorra, a second-person-voice meta-satire about generic travel writing. Perhaps fittingly, expanded versions of these two stories serve as the chapters that begin and end my new book.

Artistic considerations aside, it’s been a pretty turbulent 10 years for the business side of travel writing. This has a little bit to do with economic uncertainties, but even more to do with the rise of the internet and new media. For the past decade, and especially the past five years or so, it’s been one big guessing game in regards to what type of publication has a future. Blogs have boomed, so has online video; magazine ad space has shrunk, and traditional newspapers are suffering. Since so much travel media naturally emphasizes consumer and service information, this probably just means that the same kinds of articles are finding their way into new and different venues.

Interestingly, I don’t think the shake-up of the media world has changed literary travel writing all that much; it’s just that good writers are ending up in different venues. I think it’s really a matter of editorial vision. When Tim Cahill and company edited Outside magazine in the 1980s, they produced some amazing writing by stellar writers. The same thing happened back when Joan Tapper was helming Islands, and when Don George was editing Salon Travel. I might add that the same thing has happened with World Hum. No matter where the market shifts, publications and editors who emphasize incisive and original travel narrative are going to stand out. You see it when Travel + Leisure hands the keys to Gary Shteyngart, or when National Geographic calls on Peter Hessler.

Sadly, we’ve seen huge attrition in the editorial ranks of newspaper travel sections recently. Thomas Swick of the South Florida Sun-Sentinel and John Flinn of the San Francisco Chronicle—two of the finest travel writer-editors in America, in my opinion—are leaving or have left their newspaper positions this year. I don’t want to be pessimistic, but the sensibility they brought to their papers—the emphasis on well-written, experiential essays—could leave with them. Deeply experienced travel editors have also left the Chicago Tribune, Sacramento Bee, and Dallas Morning-News in recent months and years—just to cite a few examples. We’ll see what happens. I’m optimistic that good travel writing finds its audience one way or another.

What major changes have you noticed in travel in general?

Electronic communication has radically transformed the travel experience. Fourteen years ago I took my first vagabonding trip, eight months around North America. That was before the ubiquity of email and cell phones; communication meant sending a postcard or jamming quarters into a pay phone, which meant I was usually out of touch with family for weeks at a time. Five years later, I was paying $15 an hour to send emails from a slow dial-up connection in Luang Prabang, and it seemed like a communication miracle. By contrast, just last month I was traveling with an AT&T BlackJack in East Africa, and I could use it to call home or check my messages in Juba, Sudan. This wasn’t just a one-way thing: The people in Juba may not have much in the way of indoor plumbing, but they love their cell phones, too; I lost track of how many little thatch-roofed kiosks I saw selling phone credits.

So that’s the main transformation I’ve seen. There have been other big developments in the past decade, including the boom in online travel-planning resources and the rise (and possible fall) of cheap airfares. But communication technology stands out.

The new challenge here, of course, is learning how to wean yourself off this new technology as you travel. The charm of leaving home has always been that it transports you into new places and vivid moments; it makes you slow down and take note of your new surroundings. This can be hard to do if you’re always checking your inbox or texting your friends back home. If you can actually do that—if you can cut the electronic umbilical cord and embrace the moment on the road—travel can still be as amazing as ever.

In the introduction to “Marco Polo Didn’t Go There,” you note one of the major themes in your writing: “The challenge of identifying ‘authenticity’ in post-traditional settings.” How should travelers go about identifying authenticity? Or, at this point, is the search for authenticity just a fool’s errand? If so, what should travelers be seeking out?

In the introduction to “Marco Polo Didn’t Go There,” you note one of the major themes in your writing: “The challenge of identifying ‘authenticity’ in post-traditional settings.” How should travelers go about identifying authenticity? Or, at this point, is the search for authenticity just a fool’s errand? If so, what should travelers be seeking out?

I can’t help but think of what Thomas Merton said when people asked him if he’d seen the “real Asia” when he was in India and Thailand in the late 1960s: “It’s all real, as far I can see.”

I think that part of the challenge is that by nature we seek out cultural differences as travelers, yet we tend to project Platonic ideals onto what other cultures should look like and how those cultures should operate. This is nothing new. The ancient Greeks and Romans who traveled to Egypt projected their own exotic fantasies onto Egyptian religion and society. In turn, the young British aristocrats of the 18th and 19th centuries went to Greece and Rome and were disappointed to find unwashed peasants instead of the classical magnificence they thought they’d find there. As I say in the very first chapter of my book, “it’s the expectation itself that robs a bit of authenticity from the destinations we seek out.”

In his 1961 book “The Image,” Daniel Boorstin compared foreign countries to celebrities; we feel that we know them already, in a way, and that familiarity skews our notion of what they are supposed to be like in reality. “The tourist seldom likes the authentic (and to him often unintelligible) product of the foreign culture,” Boorstin wrote, “he prefers his own provincial expectations: The American tourist in Japan looks less for what is Japanese than what is Japanesey.” In essence, what we think is authentic is often less authentic than what we might identify as inauthentic.

Tourists aren’t the only people who fall into this pattern. In the endnotes to chapter 15, I describe meeting a Lebanese guy who, when he found out I was from Kansas, expressed a desire to come to the prairies and “ride horses with the Indians.” When I pointed out that the Native Americans I knew didn’t ride horses, he insisted that they must not be real Indians, because real Indians ride horses.

So obviously, a sense of fantasy is at the heart of most everyone’s impressions of faraway places. The only real way to get away from those fantasy-driven expectations is to try and drop your self-consciousness as you travel, to simply accept each moment for what it is. It’s something of a spiritual exercise, and—as I show in my book—it doesn’t always come easy.

“Marco Polo” looks back, but it’s not just full of reprinted stories. You’ve added a commentary track. How did that come about and what were you hoping to accomplish?

I added the “commentary track” endnotes because I wanted to hint at the ragged reality behind the creation of each story. It’s something I always wish David Sedaris or Susan Orlean or even Tim Cahill would do when they gather their previously published essays into a single collection. These writers tell us what happened in their stories, but what is it they aren’t telling us? What is it they can’t tell us, be it for reasons of story unity or personal embarrassment or opportunistic embellishment? This is nonfiction, after all, and most of what you experience in real life—including the process of writing the story itself—has to be rearranged or condensed or left out.

So I wanted to collect some of the elements that had been left out of my stories and use them to remind the reader of the gap between narrative and experience, traveler and writer, truth and presentation. I wanted to hint at how stories themselves—which by nature must be self-contained in order to be readable—emerge out of a much more complicated world of lived experience.

Again, it’s tempting to give a nod to David Foster Wallace, who popularized the use of endnotes or footnotes as a way to crinkle and deepen an otherwise linear nonfiction narrative.

Now that you’ve looked back, where do you see travel writing headed in the next decade?

In the business sense, I have no clue where travel writing is headed—though if I did, I could make a fortune as a media consultant. Consumer travel writing is paired quite closely with the travel industry, and thus is likely to wind up wherever the most readers are tuning in—be it websites, or magazines, or whatever media technology is invented next week. Literary travel writing will continue to appear wherever it is championed by individual editors and publishers, and its more specialized readership will follow accordingly.

In artistic terms, I think travel writing will always be the product of its age. As recently as one hundred years ago, for example, travel writing was characterized by detailed cultural and topographical descriptions. In an age of mass information, description is no longer enough; writers need to make connections and actively interpret the texture of places that can retain their distinct character even as they change rapidly. This applies to American flyover country as much as it does Yemen or Botswana.

It’s been said that travel literature was crucial to the evolution of the modern novel, that Victorian Romanticism emerged from a 19th-century travel boom that created a fascination with faraway places. I’d like to think that travel literature in coming decades will champion a kind of Postmodern Realism—a measured-yet-optimistic sensibility that cuts through the fantasies of tourism and the alarmist hue of international news reporting to leave us with something essentially human and true about the rest of the world.

Thanks, Rolf. Best of luck with the book, and your next decade of stories. ![]()

pelu awofeso 09.23.08 | 10:26 PM ET

This is such an excellent Q&A with Potts. I recall reading - over and again, I must say - both “Storming ‘The Beach’” as well as “The Art of writing…About Andorra” sometime ago on World Hum and the sheer delight I felt doing so.I’m not surprised the author reveals that he’s had more feedbacks from them than any other writings of his. I particularly downloaded “Andorra” for keeps. Why? I thought not having it in my collection of ‘cuttings’ would be like a farmer heading to the field without a hoe. And the cover of the new book is…breathtaking.

pelu awofeso 09.24.08 | 3:53 AM ET

This is such an excellent Q&A with Potts. I recall reading - over and again, I must say - both “Storming ‘The Beach’” as well as “The Art of writing…About Andorra” sometime ago on World Hum and the sheer delight I felt doing so.I’m not surprised the author reveals that he’s had more feedbacks from them than any other writings of his. I particularly downloaded “Andorra” for keeps. Why? I thought not having it in my collection of ‘cuttings’ would be like a farmer heading to the field without a hoe. And the cover of the new book is…alluring.

Helmut 09.24.08 | 8:13 PM ET

Yes, the cover. It’s oh so…seductive.

John Deere 09.26.08 | 6:02 PM ET

Rolf and his book cover are so….tantalizing.

JSM 09.27.08 | 10:34 AM ET

“Michael Yessis asks him how travel writing has changed in the last decade—and what he sees for the future.”

I’m surprised that there is no mention of the role and influence of television travel documentaries. If a picture is in fact worth a thousand words this,together with the lessening of availabel time for relaxation, and the consequent shortening of the attention span of many of today’s readers, there must surely be some impact on the travel writer’s job. Also will TV, recognising that its role of producing simple, ‘pretty’ travelogues, must evolve into deeper levels of travel, seek to recruit the top travel writers to scripttheir productions? Likewise, will travel writers, like fiction writers, begin to pitch their writing to attract film offers?

Robert Brown 10.08.08 | 3:42 PM ET

JSM puts me in mind of a fairly recent cartoon in the New Yorker. Husband and wife sit on the sofa, watching TV. She says, with a look of excitement and possibilities on her face, something like When we retire, let’s watch the Travel Channel.