Will Self: On ‘Psychogeography’ and the Places That Choose You

Travel Interviews: The novelist and journalist talks to Frank Bures about his new book, long-distance walking and our search for the places that embrace us

12.17.07 | 4:41 PM ET

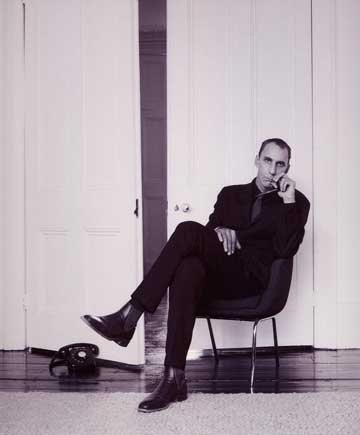

Photo by Michael Wildsmith.

Photo by Michael Wildsmith.A few years ago, acclaimed British novelist and journalist Will Self started walking. Not just wandering around, but really walking. He began after he quit using drugs, after he was famously kicked off British Prime Minister John Major’s plane in 1997 for allegedly snorting heroin in the bathroom. After that, Self began walking 10 and 20 and even 100 miles at a stretch. As a student of psychogeography, he found a kind of fulfillment in these adventures that he could not find traveling in planes, trains or automobiles. It had something to do with the way the physical world and the mind intersect to create experience, and it’s the subject of his new book, Psychogeography, a collection of his essays about his walks around the world.

In it, Self writes that people today are “decoupled from physically geography.” He observes that walking “blows back the years, especially in urban contexts. The solitary walker is, himself, an insurgent against the contemporary world, an ambulatory time traveler.” He told the New York Times on his 26-mile walk from New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport to Manhattan that, “People don’t know where they are anymore. In the post-industrial age, this is the only form of real exploration left. Anyone can go and see the Ituri pygmy, but how many people have walked all the way from the airport to the city?”

The book is one of the most original travel tomes in years. Its essays, which originally appeared in the Independent, are illustrated by none other than Ralph Steadman. It hits bookstores at a time when many people seem to be craving a more immediate experience of the world and are ready to explore experimental travel. Frank Bures asked Self all about it.

World Hum: For the uninitiated, what exactly is psychogeography?

Will Self: The term derives from the French Situationists, a post-Marxian groupuscule in 1950s Paris. Their leader, Guy Debord, coined it. For him, what he fervently hoped was that “late capitalist” society was a kind of illusion, or spectacle, in which city dwellers were thrust hither and thither by commercial imperatives—work, consume, die—and so unable to experience the reality of their environment. His solution was the derive, or drift, really a resurrection of the time-honoured tradition of the Parisian flaneur, in which the solitary walker ambles through the metropolis, experiencing its richness and diversity when freed from the need to use it. Since the Situationists—whose main derive was to pick up a few bottles of cheap red wine, get drunk on them, totter through Paris to the Ile de la Citee in the Seine and then sleep it off—psychogeography has mutated in many ways, but most of us who practice it—and it is a practice, not a field per se—take the view that by walking you can decouple yourself from the human geography that so defines contemporary urbanity.

How did you get interested in it?

My epiphany came in 1988, when one day I found myself standing in Central London with a day to kill. I realised—from out of the blue—that I had never seen the mouth of the Thames River that flows through London, even though I had been born in the city and lived there all my life. Not only that, I had never even seen a representation of it. It struck me, that if you were to encounter a peasant 30 miles from the mouth of the Amazon, and ask him what it was like at the river mouth, and he was to say that he had never seen it, you would think him a very benighted peasant. Yet that peasant was me. I immediately got in my car and drove to the mouth of the Thames. Needless to say it was nothing like I imagined. But as an indication of how strongly this human-defined geography still holds sway, I recently asked a large London audience at one of my readings how many of them had seen the Thames’s mouth, and only a handful raised their hands.

What got you started as a long distance walker?

My father was a big walker. My way of being with him was to walk. We did long walks—hikes, really—when I was a child. The impulse to walk went underground for a long while—walking doesn’t really mix well with drug addiction, unless you’re going to score—but then re-surfaced eight years ago when I cleaned up. Since then it’s been burgeoning and burgeoning.

You write that tourism is a search for a place that will embrace you. Is that partly what you’re doing with your walks?

No, not really. I’m an unrepentant Londoner, and the places that have chosen me (because I think it’s that way round: places choose you, rather than vice versa), have already done so. I think you only have room for two or three serious affairs of place in a lifetime, just as you only have emotional space for two or three serious love affairs.

Apart from your walk from JFK to New York, what have been your most memorable walks?

One that springs to mind is at the mouth of the Thames. On the north bank of the river there is a large, 10,000-acre island called Foulness, which has been a British army firing range since the First World War. It’s off limits except to those going on shore from boats. You can then walk across this eerie land that time has passed by and out on to the Thames estuarial mud, this on a Medieval causeway called the Broomway, because it’s made up of bundles of broom buried in the mud. I walked with a handful of companions over the mud for about six miles upriver, before tending back to the shore—an utterly bizarre, dislocatory and quite beautiful experience.

What separates a psychogeographic act from a stunt, or a gimmick? Is it a difference in intent, or in outcome?

I’m too old for gimmicks or stunts. The kind of psychogeography I practice really works—for me. It inspires my prose, it soothes my soul. It makes it possible for me to deal with the hideousness of the globalized man-machine matrix.

In such a hypermediated world, what room is there for an idea like psychogeography?

Like writing—which is low start-up, all you need is a pen and a piece of paper—psychogeography is bare-bones. You just get out there and experience. It doesn’t require the hypermediated world, it is more akin to a meditational practice.![]()

Photo of Will Self by Michael Wildsmith.

Joanna Kakissis 12.20.07 | 10:28 AM ET

Great interview Frank! I saw his book at an English-language bookstore in Greece and now want to buy it.

Eric Hamlin 12.21.07 | 1:51 PM ET

Thank you for reminding us that this world we live in is more than headlines and reality shows. It’s refreshing to know that something so simple, time consuming and meditative can still be embraced.

Patricia Hamilton 12.21.07 | 2:05 PM ET

I just published the Southern California edition of my book on healthy places to eat, drink wine and walk and am embarking on the Northern edition. One of my intentions is to add narrative and this has helped tremendously. California has chosen me and I’m giving back - a good story to writenow.

Felicia Shelton 12.22.07 | 11:49 PM ET

Thank you for inspiring me to do a little something different for Christmas. As I am living in and loving Seoul I will celebrate Christmas by doing something that I do every day. Walk. No parties, no small talk, just the city before me.

Paul McMillan 12.31.07 | 2:55 PM ET

The book does sound interesting, if not only to find out how a walk from JFK to Manhattan works out, but this article really doesn’t flow for me and really makes me wonder why the simple act of walking and observing needs a fancy new title.

Will’s inspiration came from driving to see the mouth of the Thames. Not walking, driving.

If he had suddenly started a walk from Westminster then that would be something and I could see the point of it being inspirational.

One of his most memorable walks is in a 10,000 acre firing range.

This has nothing to do with urban life or observing how we live whilst being freed from the need to use any of the consumerist nonsense around us.

It’s called a walk in the country! :)

Sar 12.31.07 | 7:35 PM ET

I just have to say this guy’s name is HIGHLY ironic…

HS 01.10.08 | 9:58 PM ET

As a lifelong _flaneur_ who has tramped through many cities, foreign and domestic, with and without sore feet, I really enjoyed the description of the “dislocatory” walk along the Broomway. However, amidst all the French theorizing, I believe there should be more discussion of how a place “chooses you.” It’s certainly something that has happened to me many times, and there are still places I want to go because they beckon me. Would George Moore’s concept of “echo-augury” be what’s needed here?

AzurAlive 01.11.08 | 10:44 AM ET

The wonderful and elusive aspect of the flaneurs is that they wander without any specific aim, and what’s more, they feel no need to justify their aimless loafing.

They become like water. They can’t be contained in the cusp of a hand.

Sarah 01.12.08 | 12:04 PM ET

A bike works as well. Biking, to me, is the best way to see an area, and really, it is the same concept. A low impact alternative to planes, cars, buses that put the emphasis back on the journey rather than the destination.

Bruce Stewart 02.08.08 | 2:34 PM ET

My wife and I wrote a book that uses Psycho-Geography to help people map out ways to gain direction, reach their aspirations and raise self-esteem. It is called “Your Way Home – The Psychology of Place Inside and Out.” By physically walking through a nourishing Psycho-Geography, you can definitely change your mind, uplift your perspectives and lighten your heart. All the Best!

drug rehab success stories 04.21.08 | 9:27 AM ET

Well that’s the hole point with the ironical name, it wouldn’t have had any charm with a regular name.