Daisann McLane: The Frugal Traveler

Travel Interviews: Michael Yessis speaks with the writer about the joy of travel, "travel pornography" and the lure of cheap hotels

10.09.02 | 8:23 PM ET

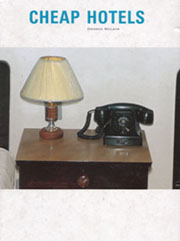

Daisann McLane writes the “Frugal Traveler” column for The New York Times and the “Real Travel” column for National Geographic Traveler. Her photo book Cheap Hotels has just been published. The photos are intimate and raw, unlike the type usually featured in glossy travel magazines, and that’s what makes Cheap Hotels memorable. McLane has captured the images and rhythms that most of us see and feel when we travel, and her accompanying text—written in English, French and German—reveals a lively side of her writing that sometimes gets buried under magazine and newspaper format constraints. McLane and I traded e-mails recently before she took off for a 10-day trip into the American Southwest.

World Hum: How did “Cheap Hotels” come about?

In the best way—serendipitously, and with the help of friends. In 2000, Nancy Newhouse, the editor of the New York Times travel section, asked me to go down to Washington D.C. to give a talk for a seminar at the Smithsonian. They’d asked our department to send people to speak at a seminar on travel writing. So I said okay, without really knowing what to talk about, and of course forgot about the whole thing until the day before I was supposed to go down to D.C.

Last minute panic took over, and I decided that a great way to eat up time and entertain the crowd would be to make a slide show for my presentation. By that point I had thousands of slide pictures that I’d taken on my travels all over the world, because in addition to writing “Frugal Traveler” I’m also the principal photographer for the column. I decided it would be funny and entertaining to pick out twenty or thirty pictures of hotel rooms I’d stayed in over the years, arrange them in reverse order according to price, from highest to lowest, and tell anecdotes about the rooms. The talk went down like gangbusters, people loved it, and I had lots of fun. And then I forgot about it.

But I’d told a good friend of mine, Karrie Jacobs, about the Smithsonian talk. At the time, Karrie was the editor-in-chief of Dwell, a magazine about modernist home design. So when Dwell was doing its summer travel issue, Karrie remembered my slide show, and wondered if I could turn it into a magazine article with photos. Sure, easy, I said. We did it, it came out good, and everybody liked it, especially Karrie’s senior editor Allison Arieff.

Allison had worked at Chronicle Books, and knew about the photo book market, something I was clueless about. She immediately got in touch with me, and said she was sure that some art or design publisher would snap this idea up if it were a book. And she was right. I was very lucky to work with a genius of a book designer, Bryan Burkhart.

It’s a terrific design. I love all the little touches—the reproduced guest signature, the chorizo sandwich icon.

Bryan, who did a gorgeous book about the Airstream Trailer, is the one who came up with all those wonderful graphic and visual touches that make it so much more than just a book of hotel room photos. We presented our proposal as an author/designer package. This way we got to keep more control over what went into Cheap Hotels. Control was an issue for me, because so much of my other public writing gets hammered and tinkered with by other people. That, unfortunately, is the name of the game in the U.S. newspaper business. I think one of the big reasons I was so excited about doing Cheap Hotels is that after four years of working in a tightly-formatted newspaper context I really wanted to hear my own unexpurgated voice in print for a change. And I enjoyed working with Bryan, who is a total visual person, so we communicated through the slide photos, through images more than words, which felt so relaxed to me. Making the book was pure pleasure.

What are some of the things about a cheap room that make you, as you write in the book’s introduction, so “unexpectedly and inexplicably” happy?

It happens when I walk into a new room and sense immediately that someone has put a piece of their heart into the room, something that reflects either a proprietor’s personality, or local culture, or in the best case, both. In the book I mention, for instance, the way that in Fiji or the Cook Islands, even the most modest hotel will have the housekeepers put fresh ginger or pikake flowers on the pillow or nightstand. The flowers, as they wilt in the heat, give off the most intoxicating fragrance. You want to swoon. In Bali, of course, you will wake up and open the door and find a little banana leaf packet filled with rice and flower petals—offering to the spirits. I always am touched to think that, so far away from home, I am being cared for by a stranger concerned with my spiritual well-being.

In the less remote, more Westernized places, the quirks of a hotel room may not be so exotic or culturally rich, but they still make a difference. In the Caribbean, for instance, I’ve stayed in a few places (two of them are in the book, one in Panama, and one on the island of Carriacou) where the owners had clearly fallen in love with the local styles and customs. They’d created rooms made of local materials, with fans instead of air conditioning, bright prints and colors. True, high-end exclusive resorts do this too, but I feel much happier when I can enjoy really beautiful surroundings without all the pretension and without worrying every time I order a beer that it will cost $10.

By contrast, nothing makes me more miserable than to have to hole up for the night in a totally impersonal place, whether it be a well-appointed Marriott or a Motel 6. A close second is to have to spend a night in one of those American bed and breakfast places that are supposed to reflect the owner’s personality but that really reflect the Bed and Breakfast Industry Catalog that the owner has used as a guide to appoint his or her inn. I’m talking about these palaces of Victorian Kitsch that are dripping in fake lace and polyester ruffles and where there are little baskets of evil-smelling gift shop vanilla potpourri tucked into every corner.

Have you always been so enamored of low-end accommodations?

I have been traveling like this for more than twenty years, just not as frequently and intensely. Before I did the “Frugal Traveler” column, I was writing mainly about world music and Latin American culture for everyone from the New York Times Arts and Leisure section to Rolling Stone to various academic publications, and even for a Japanese magazine called Latina. I also spent about four years in the 1990s working on a PhD in cultural studies at Yale, which I managed to avoid finishing (I took this job and dropped out). So I was roving a lot for work and school, and learning about calypso, merengue, Haitian voudou, son cubano, vallenato, samba and axe, North African music by traveling to other countries to meet musicians and attend music festivals. Since this work did not pay much if anything, I had to figure out ways to travel inexpensively to Colombia, Haiti, Trinidad, Brazil—and to get other people to pay for my travel. The way I got into travel writing is that I found it was often easier to sell an article, for example, about traveling to Bahia, Brazil, than it was to sell someone an article about the Brazilian religion candomble. So I’d go to Brazil to immerse myself in the music, and, along the way, grab enough info that I could also whip up a travel article. Of course, I’d make sure that I laced the travel article with my cultural interests as much as I could.

So, always, I was staying in modest accommodations, but in the places I was visiting, the alternative was to stay in the huge resort hotel or the gleaming businessman’s hotel—and in some of the places I traveled, like Port au Prince, Haiti, such places didn’t even exist. However, I would always manage to find a small, inexpensive place that was just fantastic, which put me close to the action of music, or carnival, or street food, or whatever I’d come to enjoy. In Cartagena, Colombia, for instance, I’d rent a room in some fabulous old Spanish Colonial mansion for $25 a night. And even when the inexpensive room was just so-so, it was always preferable, for me, to stay in a place that was close to the street, rather than roped off and surrounded by a fleet of overpriced taxi drivers and tour guides. In a way, such hotels turn you into a prisoner of your affluence. I also think you’re much less safe traveling like this.

How have those thoughts evolved since you signed on with the Times?

Since I’ve been writing “Frugal Traveler” my tastes haven’t changed much. If anything, having to be on the road constantly gives me a sharper sense of what I want to find in a hotel or guest room, and less patience with the cookie-cutter establishments, whether they be low end or high end, Motel 6 or Ian Schrager. I hate going into a hotel room and being reminded, by every detail of the room, from the size and brand of the soap to whether there are real light bulbs in the lamps or those cheapo fluorescent things, exactly how much I am paying for the night. When you are surrounded by little cues and signals about money and economics, rather than the personal touches I mentioned previously, your travel experience gets overwhelmed by these class issues. I suppose this is a good place to mention that I have never liked the moniker “Frugal Traveler,” which I inherited from the previous columnist and from the editors. Because “Frugal Traveler” implies that money is the central issue for a traveler like me, the main reason for staying in modest hotels and eating in homey restaurants. That you are somehow traveling handicapped because you do not have unlimited resources. I find this so wrongheaded an idea. The issue is not money. It is experience and openness. If I had a gazillion dollars to blow on, say, a trip to Japan, I’d still stay in local ryokan and Japanese Inn Group hotels where no one knows much English and so you are really forced to try to communicate with gestures and a few words of Japanese, and in the process you discover things about Japan that you wouldn’t otherwise. Negotiating your way through daily life in Japan, with as much grace and humor as you can muster, is the best part of being there! If I were being pampered and guided and translated for I would be miserable. When you travel luxe (as opposed to, ahem, “frugally”), you miss so much.

The photos in Cheap Hotels are more interesting to me than most of the images in travel magazines, and I don’t think I’m alone in feeling that way. What is it about these kinds of rooms that are so much more compelling to look at and read about than resort hotels and big chains?

Well, it’s just like with fashion models or Penthouse pinups—real women are always more interesting and sexy than the ones styled and airbrushed for mass consumption. Those fashionista high-end travel and architecture magazines, and the recent glut of super-styled hotel coffee table books, are delivering a kind of travel pornography. It is certainly amusing to look at, and flip through quickly, but I don’t think it has much sticking power because there’s a sameness to the photographs. At the end of the day, one exquisitely styled and lighted photo spread of a fabulous resort looks pretty much like another. Often it is because they are actually photographed by the same handful of photographers and designed by the same handful of interior designers, and so your suite in the Seychelles has the same light fixtures as the one in Miami Beach.

All the photos in Cheap Hotels bring back to me intense memories of these rooms that I stayed in. When I look at the photos, I can smell the rooms, remember how I slept, remember whether I was feeling happy or sad when I stayed in them. Maybe some of that emotional intensity that the pictures stir in me can also be felt by people who never went to these places but are simply looking at the photos. At least some people have told me so. It’s very mysterious how these things work, and I don’t want to spoil the karma by trying too hard to figure it out.

What are a few of your favorite photos in the book?

Ah, the question of favorites. Travel writers out there reading this, don’t you wish you had a dollar for every time someone backed you into a corner at a party and said, “But what is your favorite place of all the ones you’ve been to?” I find that question so hard, almost impossible to answer because I find something to like about almost every place I go. So much of my happiness in a particular place has to do with personal circumstances and moods, affinities that I might have or not have with a particular culture. That’s why, in Cheap Hotels, I didn’t do a chapter called “Favorite Rooms.” Instead, I did one called “Ten Places Where I Was Happy.” And then I picked the ten photos of rooms, and of views from rooms, that reminded me of moments on the road where I felt utterly content to be in that particular place, in that particular room. I don’t know if they would make other people as happy as they made me, although I hope they would. One of the things I wish is that Cheap Hotels will lead other travelers to these little remote spaces of contentment. They may not necessarily be the ones I found. But perhaps Cheap Hotels will inspire the readers to go out and find their own happiest rooms. Okay, okay, so I’ll get specific. As far as photos go in the book, I really like the one of the Reichstag in Berlin, covered in cranes and scaffolding, as seen through the window of my little guest room in East Berlin. It just distills, in one glance, what it feels like to be in Berlin at this time—a Berlin under construction, reinventing itself. The cover photo, which is a detail from a funny little dusty 1940s style hotel I stayed in, in Sao Luis, Brazil, always cracks me up—the old style phone, the plastic over the lampshade. The essence of Cheap Hotel. Speaking of Brazil, I also love the photo of Manaus that I took from the window of my room at the Best Western. A storm is coming over the Amazon, and the sky is an eerie blueish gray, and the town below looks raffish and wild, like Wyoming must have been in the 1860s.

And I love the little shot of my room at the Peachy Guest House in Bangkok. I’ve got my junk all strewn over the place, and so it reminds me of how I was living in Bangkok. I took that shot for my own pleasure, because the New York Times photo editor would never run a shot of a “lived in” room, I have to shoot at least one round of my room before I sleep in the bed. My self-portrait, at the end of the book, was also taken in the Peachy.

And I love the little shot of my room at the Peachy Guest House in Bangkok. I’ve got my junk all strewn over the place, and so it reminds me of how I was living in Bangkok. I took that shot for my own pleasure, because the New York Times photo editor would never run a shot of a “lived in” room, I have to shoot at least one round of my room before I sleep in the bed. My self-portrait, at the end of the book, was also taken in the Peachy.

I bet you come across some scary, nasty rooms. What’s the worst you’ve seen?

If they’re really, really bad, I walk away and find another place to stay. Sometimes that isn’t possible. Once I went to the town of Kanchipuram, in Tamil Nadu. It is the center of some of the most exquisite silk weaving in all of India—every bride wants a Kanchipuram silk wedding sari. It also has over 100 Hindu temples, an amazing amount for a small town. And so I was really excited to go there, and figured it would have at least a minimal standard tourist hotel, and maybe something a bit better (because of all the silk merchants coming to do business).

But when I got to town, and checked into what seemed to be the best place there—it was called something like “Hotel Splendid” and cost perhaps $10 or $12—I found a room with the concrete walls soaked and mildewed. The air conditioner was a decorative rather than functional item, and the bedsheets were completely brown, as if they’d been washed in tea, and had weirdly shaped holes everywhere, as if someone had chewed them. I was exhausted and sweaty from a long bus trip, and just devastated that the room was so, so grungy. I got the manager, and asked him to give me some new sheets. Meanwhile I went into the bathroom and discovered the water wasn’t running—a call to the desk produced a long-winded apology and the horrible news that water didn’t run from 2 to 6 p.m. in the hotel. Eventually, a bellhop came by with a stack of carefully folded, recently laundered sheets and towels—as brown and full of holes as the set on my bed!

So I stormed out into the hot afternoon streets of Kanchipuram determined to find a place where I didn’t have to cringe in order to lie in bed. But in a short while, I realized that I was already in the Hilton, as far as this town was concerned—the other guest houses were little cheap warrens of cubicles with no windows. While I was fretting about my situation, walking up and down the streets, something quite extraordinary happened. First, a woman approached me, and in halting English, asked if I wanted to visit the temple with her. She ended up taking me to her family’s house for a cup of tea. It was a very poor house, but one of her brothers ran out to get orange soda and some nuts. I stayed for a polite time, worried about them overextending themselves to a guest. I gave all my ink pens to the children, and then said goodbye and went back out onto the street.

The silk shops had opened again, after afternoon siesta, and I decided to cheer myself up by going shopping. Anything but go back to the hotel room. Well, the merchant who ended up selling me two exquisite saris then invited me to his home for dinner. I ended up spending most of the evening eating a terrific South Indian feast with him, his wife and mother and father. When I returned to the horrible room that night I didn’t care about the sheets at all. In fact, I was glad it had been so dismal, because otherwise I would have napped instead of going out and having all those great adventures that day in Kanchipuram.

I revere Bill Bryson’s books because he exhibits that same type of wandering spirit. Do you have any other suggestions on maximizing your travel experiences?

It is really important to make yourself as open and approachable as you can. Obviously this is something you can’t do all the time, for safety and comfort issues. But I think you really get a lot more out of a place when you assume the best of people rather than the worst, when you smile and are extremely polite, when you let things flow as opposed to imposing your own needs and schedule and timetable on other people who may not really understand your urgency. If the bus sits in the station for two hours, you just have to chill, really.

Another really important thing, for me anyway, is language. I speak Spanish fluently, can fake my way in Portuguese or Italian, and I’ve just spent a year learning Cantonese, and studying Chinese characters. In other places, I try to learn a couple of phrases of the local language, even if it’s only please and thank you. This is so, so important. It changes everything about your travel experience to have a couple of phrases for those moments you get lost, or need help. You feel more confident. And it helps, I think, combat that impression that many foreigners have around the world of Americans being arrogant and self-involved, thinking that everyone must speak English. If I had a Bill Gates fortune to give away, I’d start a foundation to support and encourage foreign language training in U.S. schools. I think it would change our society in the most wonderful ways if kids were encouraged to get fluent in one or more foreign languages.

Your National Geographic Traveler “Real Travel” column continues the epic travel/tourist debate. Do you think we need to pick sides? Can’t we be both?

The traveler versus tourist label is the subhead the editors put on the column, it doesn’t really reflect my thinking on the subject. But it was an easy, shorthand way I suppose to communicate to a general, mixed audience of readers that my column wasn’t going to be about finding “hot” destinations, the latest resort hotels, or a cheap airfare on the Internet. If it takes a bit of packaging to slip some real life stories and thoughts about travel into a major mass-market travel magazine, then I say, package away. I give National Geographic editor in chief Keith Bellows major props for bringing a wide range of issues and perspectives on travel into Traveler—as far as I can see, he is the only editor of a major U.S. travel magazine who is trying to foreground actual travel, rather than design, fashion, or conspicuous consumption. Given the context of travel publishing in the U.S. Keith’s approach is downright radical. I feel honored to be part of the magazine (and especially because I grew up reading National Geographic in the 1970s, pining to go to all those places), and I cross my fingers that current world events will encourage Americans to really go out and explore and get to know the unfamiliar, rather than fly thousands of miles to stay in enclave resorts that insulate them from it. When I write the “Real Travel” columns I’m trying, through stories and anecdotes, to let people know it is really okay, in fact, much more than okay, to venture outside the pre-fab world of tours, hotels, of “attractions.”

Amen.

But back to “tourist.” There is a huge academic literature on “tourism,” and by its definition I am a tourist. In the context of travel writing, however, the word takes on a different connotation. We think a “traveler” is cool, the “tourist” is not, and there’s a lot of snobbery attached to identifying oneself as the former. But I think we should let that go. We are all tourists. If you can afford a round trip ticket to Laos, and you go there for personal stimulation, not for a job, even if you end up staying for six months on the floor of a Hmong hut in a remote village, you’re still a tourist.

The larger question is: What kind of a tourist are you? There are so many different ways to be, when you are away from your own place, out of your own context. Some of these ways maximize your contact and exchange with other people. Others keep you for all intents and purposes wrapped in the security blanket of home, looking at the world through a safety screen. And I suppose that when we say “tourist,” with a sneer, we are talking about these people, the ones who, whether in Rome or Rio, live more or less the same way they do in Pasadena.

Most of us probably fall somewhere between those extremes of tourism, neither sleeping with villagers on mud floors nor following a little man with a whistle and a flag around Venice. I think that there are a lot of people out there located, more or less, on the same part of the tourist spectrum as me—not averse to floor sleeping now and then, but who enjoy a hot shower and a good, strong cup of coffee in a garden filled with mango trees and hummingbirds. Who will choose the hotel without air conditioning because every room has a lazy ceiling fan and French windows that open to a vista of ancient temples. Who will go to Angkor Wat and afterward remember, far more vividly than any ancient ruined temples, the afternoon that their guesthouse owner sat down with them over coffee and told them the story of his escape on foot from the Khmer Rouge.

Too many travel editors, especially the ones at American newspapers, think that this approach to travel is novel and eccentric, something practiced by a fringe group of tourists. They think that most of their readers take tours and cruises and go to big museums and Michelin restaurants and obsess about airfares because that is the kind of letter that shows up in their mail. And so my kind, our kind, of tourism gets slotted into sidebars or specialties like “Frugal Travel.” I would like to think that they are wrong, and that the reason they don’t get letters from us is because we are having too much fun on our journeys to bother to write. Maybe we should, so that the editors would get a clue!

Good idea. We’ll have to organize a campaign. Final thoughts?

I really hope that Cheap Hotels will find a place on the bookshelves of my imagined community of coffee drinking, ceiling fan loving, sutra chanting, Hong Kong TV soap opera loving, fractured-Japanese-speaking fellow tourists.![]()

All photos courtesy of Daisann McLane, from her book Cheap Hotels.