Destination: Asia

Pico Iyer on Japan’s ‘Sadness That Will Not Go Away’

by Michael Yessis | 12.29.11 | 7:46 AM ET

Like Daisann McLane in her three-part series about Japan in the wake of its triple disaster, Pico Iyer has captured a haunting snapshot of life in the country post-earthquake and tsunami. He writes for Businessweek:

When I went up to the area around the nuclear plant in October, I found myself staying in, of all places, a golf resort by the sea. Many of the locals had left the area after the disaster, I was told. When I arrived, late at night, the big hotel looked like a ghost town. Only a handful of kimono-clad guests seemed to be enjoying the tea lounge and the play area.

Next morning, I awoke early and went into the breakfast room at 6:15—to find every table packed. Dapper golfers from Tokyo were busy scarfing down their eggs, about to head out for their first round, undeterred by pelting rain and the belching factories that surround the seaside course. In some places this could look like recklessness or indifference; in Japan it seemed to stand for fortitude.

(Via @gary_singh)

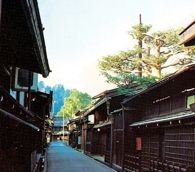

Journey to High Mountain

by Tara Austen Weaver | 12.13.11 | 12:36 PM ET

In an e-book excerpt, Tara Austen Weaver finds a new home in rural Japan

Interview with Henry Rollins: Punk Rock World Traveler

by Jim Benning | 11.02.11 | 12:40 PM ET

Jim Benning asks the musician about his new book of photographs and how travel has humbled him

Electronic Surveillance Abroad: ‘Sophisticated and Pervasive’

by Michael Yessis | 09.27.11 | 5:16 PM ET

Also: A little scary. Ellen Nakashima and William Wan illuminate the conditions business travelers and government officials are presumed to face when traveling to China and some other countries. From the Washington Post:

Security experts also warn about Russia, Israel and even France, which in the 1990s reportedly bugged first-class airplane cabins to capture business travelers’ conversations. Many other countries, including the United States, spy on one another for national security purposes.

But China’s brazen use of cyber-espionage stands out because the focus is often corporate, part of a broader government strategy to help develop the country’s economy, according to experts who advise American businesses and government agencies.

“I’ve been told that if you use an iPhone or BlackBerry, everything on it—contacts, calendar, e-mails—can be downloaded in a second. All it takes is someone sitting near you on a subway waiting for you to turn it on, and they’ve got it,” said Kenneth Lieberthal, a former senior White House official for Asia who is at the Brookings Institution.

One anonymous security expert buys a new iPad when s/he visits China, then never uses it again.

Buzkashi, Revisited

by Michael Yessis | 09.13.11 | 10:57 AM ET

The Lunatic Express author and World Hum contributor Carl Hoffman looks at how buzkashi, Afghanistan’s goat-based national sport, has changed since 9/11.

What was originally a pickup game played at weddings and festivals has become a game of one-upmanship between rich big men getting richer and bigger every day. Who has the most horses? The most expensive horses, which can cost $50,000 in a country where the average annual wage is $370? The best stable of chapandazan? Players have always been sponsored—given good horses to ride for the glory of the horse’s owner and small profit for the rider—but now a few have made themselves the world’s first professional, full-time buzkashi players.

We published David Raterman’s story about buzkashi, aka buskaschee, in 2002. He recently drew from the story for a scene in his novel, The River Panj.

A World Hum Story is Novelized

by Jim Benning | 09.09.11 | 10:20 PM ET

David Raterman drew from his 2002 World Hum story Down by the Buskaschee Field about Tajikistan while writing “The River Panj,” described as “the first thriller to open in Afghanistan on 9/11.”

From a press release:

On Sept. 11, 2001, ex-Notre Dame football star Derek Braun is doing relief work in Afghanistan when his fiancée and elderly colleague are kidnapped along the border with Tajikistan. With no one to help, he goes in search. On this dangerous journey, he faces Islamic terrorists, heroin smugglers, corrupt Russian soldiers, Iranian spies and helpless CIA agents, witnessing an assortment of terrible acts that culminate in his own kidnapping.

The novel, which promises to be the first in a series, is available in paperback for $10.99 here and as an e-book for $2.99 on Amazon and iTunes.

By the way, you have to love a writer who devotes a section of his website to publishing rejections. They’re enough to give any aspiring novelist serious pause.

Ai Weiwei’s Beijing

by Michael Yessis | 08.30.11 | 12:37 PM ET

The Chinese artist has broken his post-detention silence in a piece for Newsweek. He writes of Beijing:

I feel sorry to say I have no favorite place in Beijing. I have no intention of going anywhere in the city. The places are so simple. You don’t want to look at a person walking past because you know exactly what’s on his mind. No curiosity. And no one will even argue with you.

None of my art represents Beijing. The Bird’s Nest—I never think about it. After the Olympics, the common folks don’t talk about it because the Olympics did not bring joy to the people.

There are positives to Beijing. People still give birth to babies. There are a few nice parks. Last week I walked in one, and a few people came up to me and gave me a thumbs up or patted me on the shoulder. Why do they have to do that in such a secretive way? No one is willing to speak out. What are they waiting for? They always tell me, “Weiwei, leave the nation, please.” Or “Live longer and watch them die.” Either leave, or be patient and watch how they die. I really don’t know what I’m going to do.

‘So Everyone You See Here That’s Over 35 Lived Through the War?’

by Eva Holland | 08.04.11 | 8:58 AM ET

Over at Matador, World Hum contributor Lauren Quinn wrote a long, layered story about a visit to the Killing Fields in Phnom Penh, her childhood friendship with the daughter of expat Cambodian survivors in Oakland, and the silence that seems to linger over the war.

Here’s a taste:

Our tuk-tuk rattled along the unsteady pavement, taking us closer to the mass-grave execution site that is one of Phnom Penh’s two main tourist attractions. The other is the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, the former S-21 torture prison under the Khmer Rouge. All the travel agencies along the riverside advertise for tours of the two, sometimes combined with a trip to a shooting range where travelers can fire AK-47s left over from the war (ammunition costs not included).

Most travelers stayed in Phnom Penh only long enough to see S-21 and the Killing Fields, then scattered from the city. It was what Cindy was doing, and what I, if I hadn’t come for my particular project, would have done as well. I’d been putting off visiting the Killing Fields, not wanting, I’d rationalized, to spend the $12 tuk-tuk fare venturing out solo. Cindy offered an opportunity to split the cost—but more than that, she offered a buffer, a companion.

The wind grew stronger without buildings to block it, and I blinked bits of dust and debris from my contact lenses. By the time we pulled into the dirt lot in front of the Killing Fields, stinging tears blurred my vision.

“This happens every day here,” I laughed, and dabbed my eyes.

Rebuilding the Bamiyan Buddhas

by Eva Holland | 07.27.11 | 5:16 PM ET

The famous Afghan statues were demolished by the Taliban in 2001. World Hum contributor Joanna Kakissis reports on the painstaking rebuilding process for NPR:

Up to half of the Buddha pieces can be recovered, according to Bert Praxenthaler, a German art historian and sculptor, who has been working at the site for the past eight years. He and his crew have sifted through 400 tons of rubble and have recovered many parts of the statues along with shrapnel, land mines and explosives that were used in their demolition.

But how do you rebuild the Buddhas from the rubble?

“The archaeological term is ‘anastylosis,’ but most people think it’s some kind of strange disease,” said Praxenthaler.

For those in the archaeology world, “anastylosis” is actually a familiar term. It was the process used to restore the Parthenon of Athens. It involves combining the monument’s original pieces with modern material.

(Via @juliaindc)

Pakistanis Don’t Approve of U.S., but They Love its Fast Food

by Michael Yessis | 07.25.11 | 12:11 PM ET

The new Hardee’s in Islamabad is wildly popular. McDonald’s expanded to home-delivery. A sports bar serving chicken wings—though not beer—just opened. Nicolas Brulliard explains what’s going on:

Nowhere is Pakistanis’ love of American fast food more apparent these days than at the newest Hardee’s. A few days after a much-hyped opening attended by U.S. Ambassador Cameron Munter and his wife, lines of customers still extended outside the doors. Nawaz Sadiq, manager for development and training at Hardee’s, said the outlet has served an average of 5,000 to 6,000 customers a day so far.

“The Pakistani market is very much brand-conscious,” Sadiq said. “Pakistani people are against America because of its policies, but at the same time, people want quality.”

Unlike in the United States, fast food here is among the more expensive eating-out options. At 390 Pakistani rupees, or about $4.50, a Big Mac is out of reach for most people. Consequently, many customers are part of Pakistan’s highly educated class and have spent time in the United States, or have at least more favorable opinions of the United States than most of their countrymen.

To China’s Fangji Cat Meatball Restaurant and Beyond

by Michael Yessis | 07.18.11 | 11:18 AM ET

More travel-related hilarity from David Sedaris in China, though it’s not for those without an adventurous palate. And if you do have an adventurous palate, Sedaris salutes you:

Another of the dishes that day consisted of rooster blood. I’d thought it would be liquid, like V8 juice, but when cooked it coagulated into little pads that had the consistency of tofu. “Not bad,” said the girl seated beside me, and I watched as she slid one into her mouth. Jill was American, a Peace Corps volunteer who’d come to Chengdu to teach English. “In Thailand last year? I ate dog face,” she told me.

“Just the face?”

“Well, head and face.” She was in a small village, part of a team returning abducted girls to their parents. To show their gratitude, the locals prepared a feast. Dog was considered good eating. The head was supposedly the best part, and rather than offend her hosts, Jill ate it.

This, for many, is flat-out evil but the rest of the world isn’t like America, where it’s become virtually impossible to throw a dinner party. One person doesn’t eat meat, while another is lactose intolerant, or can’t digest wheat. You have vegetarians who eat fish and others who won’t touch it. Then there are vegans, macrobiotics and a new group, flexitarians, who eat meat if not too many people are watching. Take that into consideration and it’s actually rather refreshing that a 22-year-old from the suburbs of Detroit will pick up her chopsticks and at least try the shar pei.

Mother Jones Goes to ‘Culture Training’ at an Indian Call Center

by Eva Holland | 07.15.11 | 10:02 AM ET

In the latest Mother Jones, Andrew Marantz has a fascinating story about his brief stint as a worker at a call center in India. Here’s Marantz on the mandatory “culture training” that workers undergo before they hit the switchboards:

Indian BPOs work with firms from dozens of countries, but most call-center jobs involve talking to Americans. New hires must be fluent in English, but many have never spoken to a foreigner. So to earn their headsets, they must complete classroom training lasting from one week to three months. First comes voice training, an attempt to “neutralize” pronunciation and diction by eliminating the round vowels of Indian English. Speaking Hindi on company premises is often a fireable offense.

Next is “culture training,” in which trainees memorize colloquialisms and state capitals, study clips of Seinfeld and photos of Walmarts, and eat in cafeterias serving paneer burgers and pizza topped with lamb pepperoni. Trainers aim to impart something they call “international culture”—which is, of course, no culture at all, but a garbled hybrid of Indian and Western signifiers designed to be recognizable to everyone and familiar to no one. The result is a comically botched translation—a multibillion dollar game of telephone. “The most marketable skill in India today,” the Guardian wrote in 2003, “is the ability to abandon your identity and slip into someone else’s.”

(Via Where Am I Wearing)

The Partridge Family Meets Ken Kesey on the Grand Trunk Road

by Michael Yessis | 06.27.11 | 11:41 AM ET

James Parchman spent days on a Pakistani stretch of the fabled Grand Trunk Road, wowed by the ornate decorations he saw on so many passing vehicles. The “panorama of red, yellow and green, mixed with plastic whirligigs, polished mahogany doors and gleaming stainless steel cover plates,” he writes, is part pride of design, part advertising expense.

Durriya Kazi, an artist and teacher in Karachi, has long been a proponent of Pakistan’s folk art. She sees bus and truck decorating as an integral part of that tradition, noting the importance of distinguishing between sculpture as defined by the art gallery and the rich activity of actually making things that exists all over Pakistan.

In 2006, Ms. Kazi was instrumental in a program intended to spread Pakistan’s bus decoration skills to Melbourne, Australia, where a tram was transformed into a replica of a minibus used on Karachi’s W-11 route, resplendent in all its finery.

Another Pakistani with expertise in the subject is Prof. Jamal J. Elias of the University of Pennsylvania, the author of “On Wings of Diesel: Trucks, Identity and Culture in Pakistan” (Oneworld, 2011). His book explores the tradition of Pakistani truck decoration, and looks into the “nature of response to religious imagery in popular Islamic culture.”

A terrific slideshow accompanies Parchman’s piece.

For another look at the Grand Trunk Road, check out Jeffrey Tayler’s five-part series, Cycling India’s Wildest Highway.

China Beyond its Borders

by Michael Yessis | 06.17.11 | 11:08 AM ET

Caught up with NPR’s series about the ways China is asserting itself throughout the world. It’s excellent. The latest piece looks at Italian response to the changing textile scene in Tuscany, “home to the largest concentration of Chinese residents in Europe.”

Sylvia Poggioli says:

On Via Pistoiese, shops are Chinese—hairdresser, hardware store and supermarket. There are few Italians. It’s 2 p.m. and all shops are open—there’s no time for siesta in Chinatown.

From Mandalay to Timbuktu: Great Names, Lousy Places

by Jim Benning | 06.09.11 | 12:31 PM ET

In an excerpt from his new book, “The Tao of Travel,” Paul Theroux recalls a number of places that just didn’t live up to the romance evoked by their names:

Mandalay: an enormous grid of dusty streets occupied by dispirited and oppressed Burmese, and policed by a military tyranny.

Tahiti: a mildewed island of surly colonials, exasperated French soldiers and indignant natives, with overpriced hotels, one of the world’s worst traffic problems and undrinkable water.

Timbuktu: dust, hideous hotels, unreliable transport, freeloaders, pestering people, garbage heaps everywhere, poisonous food.

I was always drawn to Kuala Lumpur because of its name. I loved just saying the words, and I loved the way they sounded. I loved the way they evoked lumpy koala bears, or something even more exotic that I couldn’t even begin to imagine.

When I finally went there, I was initially underwhelmed. The Petronas Towers are impressive, but they’re not lumpy koala bears. After exploring the city for a couple of days, however, getting lost in Indian neighborhoods with sari shops and aromatic cafes, and even spending a couple of hours in an elegant old theater watching a Bollywood movie I couldn’t understand, I decided Kuala Lumpur had its lumpy charms.

Ever gone to a place that didn’t live up to its great name? Or that did?